Topic:

Resource type:

Authors:

Publication date:

Date added to Learning for Involvement:

Introduction

Welcome to the third, and final, instalment of our series of publications highlighting co-production in action. In each series contributors show how the key principles and key features outlined in our earlier work Guidance on co-producing a research project have found expression in practice. You can find the previous publications here:

This publication has been produced by Wessex Institute on behalf of the NIHR.

About the examples

The first example is a NIHR funded project undertaken by St George’s, University of London, Population Health Research Institute. The ENRICH study is investigating the effectiveness of peer support being offered to people who are being discharged from hospital as a mental health inpatient. People with their own lived experience of peer support and living with mental health problems are working together with clinicians, academics, researchers, health professionals from statutory, non-statutory and voluntary organisations. Our second example ‘The Ideal Ward Round’ is from University of Nottingham, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, My Rights, POhWER. This project was led by people with lived experience of care and treatment in adult in-patient mental health services, who worked with carers, advocates, mental health professionals and academic researchers and developed a set of recommendations that would lead to improvement in ward round processes, outcomes and experiences for those who attend ward rounds. The final example is from patient advocates and the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre, University of Nottingham, and involves a James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership (PSP) Steering Group. The example describes a JLA PSP for mild-to-moderate hearing loss in adults which was co-ordinated and led by patients, clinicians and their advocates.

We hope that this publication, along with others in the series, bring the principles and features to life and inspire people to embark on their own co-production journeys.

Below are the key principles and features of co-producing a research project and which are referred to throughout this publication.

Key principles

- Sharing of power – the research is jointly owned and people work together to achieve a joint understanding

- Including all perspectives and skills – make sure the research team includes all those who can make a contribution

- Respecting and valuing the knowledge of all those working together on the research – everyone is of equal importance

- Reciprocity – everybody benefits from working together

- Building and maintaining relationships – an emphasis on relationships is key to sharing power. There needs to be joint understanding and consensus and clarity over roles and responsibilities. It is also important to value people and unlock potential

Key features

- Establishing ground rules

- Ongoing dialogue

- Joint ownership of key decisions

- A commitment to relationship building

- Opportunities for personal growth and development

- Flexibility

- Continuous reflection

- Valuing and evaluating the impact of co-producing research

The project team

Gary Hickey (Wessex Institute), Simon Denegri (The Academy of Medical Sciences), Gill Green, Doreen Tembo, Katalin Torok (all NIHR), Sally Brearley (Kingston University), Tina Coldham (Mental Health User Consultant), Sophie Staniszewska (University of Warwick) and Kati Turner (St George’s, University of London).

ENRICH (Enhanced discharge from inpatient to community mental health care)

(NB: The ENRICH project ran from 2015-2020. This example was originally written in 2018, with final edits being made prior to publication in 2020).

Natalia Banach; James Byrne; Lucy Goldsmith; Rhiannon Foster; Charlotte McWilliam; Rosie Morshead; Katy Stepanian; Rebecca Turner; Anna Verey, Service User Researchers

Sarah Gibson; Kati Turner, PPI/Co-production Co-leads

Jacqui Marks, Trial Manager

Steve Gillard, Chief Investigator

Organisations involved in the research:

St George’s, University of London, Population Health Research Institute (Sponsor). There are 7 NHS mental health Trusts involved as trial sites.

Summary of the research:

The ENRICH study is a five year National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) programme of research investigating the effectiveness of peer support being offered to people who are being discharged from being in hospital as a mental health inpatient and for the first few months after that. The study will also explore the impacts on peer workers of working in the role and seek to identify the principles underpinning one-to-one peer support.

ENRICH is made up of 5 work packages:

- Producing a peer support handbook and training programme. This will be achieved by reviewing the existing research about peer support and through working with people involved in doing peer support at our partner NHS Trusts.

- Developing a fidelity index – this is a set of questions designed to assess whether the peer support provided in each of the seven Trusts reflects the principles and values of peer support.

- Piloting peer support for discharge – testing whether a full trial is viable.

- Trialling peer support for discharge – this part of the study is a randomised controlled trial (this is where half of people agree to take part in the research are randomly assigned to receive peer support and the other half the usual support for discharge so that we can make a fair comparison of peer support and usual support services).

- Studying the impact of peer support. This involves using questionnaires and in depth interviews to collect data from peer workers, peer worker coordinators and supported peers who have received peer support (please refer to glossary at the end for a description of these roles). This will enable us to find out more about how the peer support works.

ENRICH is a national study, involving seven sites across England, aiming to recruit 590 participants in total.

People with their own lived experience of peer support and living with mental health problems are working together on the research with others from a variety of perspectives and areas of expertise – clinicians; academics; researchers; health professionals from statutory, non-statutory and voluntary organisations. Those with lived experience have been involved in developing the methods of investigation and the Public and Patient Involvement (PPI) strategy embedded in each phase of the research and will be involved in managing and undertaking the research alongside researchers working from other areas of expertise.

The project is still in progress and due to finish in 2020. Co-production was planned for all stages of the project, however, in practice, we have found that in later stages of the trial, there has been little opportunity for service user researchers (SURs) to feed in lived experience, especially for those members of the team who have joined later in the project or who are based away from the lead site. This is something we have reflected on as a team and intend to consider in the writing up stages so that SUR voices can be heard, and learning points are shared.

Please see the glossary for an explanation of the various lived experience groups involved in the research.

Find out more about the ENRICH research

How did the key principles of co-producing research find expression in your research?

Sharing of power

We hold whole research team meetings as well as smaller sub-team meetings regularly as a platform for power sharing at all levels of the study. We have devised and established ground rules within team meetings and have tried to accommodate those working remotely by arranging meetings convenient to the wider team and facilitating conference calling. Where full attendance is not practical/possible, decisions have been shared with the wider team for input and comment. Efforts have been made to inculcate newer members to existing work streams and give them equal power in subsequent decisions (e.g. revising fidelity index questions). Our intention is that the knowledge and insight of all people involved shapes the way in which the research is done, although this is not always easy in a randomised controlled trial.

We believe that the experiential knowledge brought by SURs and lived experience advisors should inform key decisions alongside clinical and more traditional academic knowledge. We have managed to do this with some of our strategic decisions. For example, in deciding about participant inclusion criteria for the trial, a number of the methodologists on the team thought we should restrict this by diagnosis as trial findings would be clearer and easier to communicate (and publish!), while team members with personal experience of peer support felt that would undermine the more social (non-medical) ethos of peer support. The latter view prevailed with the provision that people in diagnostic groups would be equally randomised to peer support and treatment as usual to ensure that the trial was balanced. In other words, both parties brought knowledge and power to that decision.

We also managed to share power on an operational level around much of the key development work before the trial started. Our National Expert Panel (NEP) – the people developing, leading and doing peer support – were instrumental in developing the ‘ENRICH peer support principles’ framework which guides the research, and our Lived Experience Advisory Panel (LEAP) and Local Advisory Groups (LAGS) played a crucial role, alongside SURs, health and clinical psychologists and others, in developing the peer support and book and training programme (the trial intervention).

Once the trial was running we found it much harder to share power, to co-produce the research. Trials have very rigid methods and most of the decisions about the trial itself had already been made at the funding application stage, a long time before the SUR team came into post. Experiential knowledge had been integrated into that process, but we knew a lot less about peer support and trials then and would have benefited from time and flexibility early in the project to reconsider some things.

Including all perspectives and skills

The ENRICH team is made up of: a chief investigator; SURs; peer workers; voluntary sector organisations; psychiatrists; psychologists; nursing academics; statisticians; health economists; Public and Patient Involvement (PPI) leads; a Lived Experience Advisory Panel; Local Advisory Groups; a National Expert Panel and a Programme Steering Committee (PSC).

We have structures in place to provide support/accessibility for the LEAP and our SUR team. There are 10 places on the LEAP; we ring-fenced two of these for people who were bringing lived experience and expertise of peer support in Black, Asian and Ethnic Minority communities. We would expect to be talking to each person individually about the language they use to describe themselves and the experience and expertise that they bring: no one is expected to represent or speak for ‘a community’.

Diversity runs through all the ENRICH principles and was a specific focus of one of the eight training days for peer workers. The ENRICH handbook for the peer support specifies that recruitment of peer workers should take place through community organisations (as well as through the Trust) in order to try and recruit a team that reflects the local community. We were successful in doing this in East London although this hasn’t always been possible with such small peer worker teams at each site and it has been a challenge to recruit peer workers who reflect the diversity of the local communities. For instance, in our Bradford site both peer workers are white with neither speaking a community language; this has therefore meant that the research is not accessible to people who do not speak English (as they can’t access the peer worker intervention). In Sussex, our peer workers are exclusively white, and substantive posts have been taken exclusively by women. In this way our efforts to co-produce our research may not have translated into involving local communities in co-delivering the peer support.

Respecting and valuing the knowledge of all those working together on the research

This is embedded within the team ethos and was explicitly stated at the outset. One example of this is lived experience input into the Trial Management Group (TMG) – a group that meets monthly to monitor and manage the trial – and the Data Management and Ethics Committee (DMEC) – an independent committee that reviews safe and proper conduct of the trial and also the Programme Steering Committee (PSC) The inclusion of someone with lived experience is unusual for these groups and we have adapted standard terms of reference to include this representation.

Within the team we work flexibly, open to any team member making contributions from their perspective or skills where relevant. This is supported by the use of a relatively flat power structure which enables contributions, for example, with the chief investigator and trial statistician working directly with the SUR team on many issues. We know that including all perspectives and skills is time consuming – we arrange additional meetings to include all team members in decision making and development of research materials as necessary and circulate work in development across the team for comment. However, opportunities to include all perspectives and skills close down as well as open up at particular stages of the project. For example, final discussions about outcomes to be included in the trial were curtailed because of the need to register the trial protocol within a particular timeframe.

Reciprocity

Our study is about peer support. Reciprocity is a key feature of peer support, which has been described as a two way relationship with both parties learning from each other (rather than the professional imposing their knowledge on the person they support). We try and emulate this in the way we do the research. For example, when we were developing the peer support handbook for the trial we learnt a huge amount about peer support from the trainee peer workers who attended the pilot training. More recently our SURs have fed what they have learnt from our participants about the way that peer support is working on the ground into our data collection and analysis plans.

The researchers working from lived experience have valued the opportunity to disclose and share these experiences within the context of the work they are doing. They have also valued being able to explore how this lived experience impacts on the research they are doing.

Building and maintaining relationships

This is a vitally important part of co-production and we are very aware as a team of the need to commit time and resources to this. Spaces are created within the research cycle for discussion, dialogue, reflection and team building, all things which we hope foster close and productive working relationships within the team. There is an acknowledgement that roles will evolve and change as the project progresses and we try to make sure we adapt as a team to this. This is an area which demands time and commitment and can easily come under pressure with project deadlines. We discovered – the SUR team told us – that we needed to be more organised in managing day to day research tasks so that we could make time to bring the team together.

The project involves a collaboration between a number of voluntary sector organisations, NHS Trusts and universities. In order to manage different perspectives and goals, we have a variety of meetings at individual sites (e.g. Local Advisory Groups) in order to respond to local needs and provide opportunities for relationship-building, and centrally (e.g. SUR meetings, Trial Management Group, etc.). Marking out enough time for meetings is important but poses challenges with such a busy project over multiple sites. One example is with the LEAP: we hold meetings on average only once every six months. Because of this, members have told us it is easy for them to feel out of touch with the project so we now send them monthly email updates about the project. When it comes to the meetings themselves, we always include lunch and breaks so there is the opportunity for members to catch up with each other and members of the ENRICH team on a more relaxed and informal basis.

The passion, commitment and enthusiasm we all bring to the project can both raise the heat of discussions, but also provides the key to resolving issues, through understanding the perspective of another and the reasons for their commitment to that perspective. Through such discussions, synergy is achieved.

How did the key features of co-producing research find expression in your research?

Establishing ground rules

Ground rules exist for LEAP, SUR and NEP meetings but not for whole team meetings. We set out our co-production principles at the outset as some team members were new to this approach. Here are the ground rules for the LEAP (agreed by members at the first meeting):

- If you need support to take part please say so

- Time out is ok

- Listen as well as speak – make space for others

- Everyone should be able to speak if they want to

- Respect each other’s point of view

- Value the different types of lived experience, skills and expertise we bring

- Confidentiality – personal information stays in the room

- Keep it relevant – let’s focus on what we are doing

- Be honest and tactful

- ‘Jargon Busting’ is a good thing! – point out jargon to keep language clear

Ongoing dialogue

We provide regular updates for LEAP members and have established ongoing dialogue with the LAGs as the trial gets underway at each of the study sites. There is an ongoing dialogue with core research team members (the majority of the co-applicants; the trial manager; the chief investigator and the SUR team) via the TMG but we had to build back in some dedicated co-production spaces to ensure that the SUR team continued to be involved in producing the research, rather than just doing it. We discovered that this wasn’t just about having meetings to talk about co-production, but about making sure that we had the relevant people around the table when we made decisions about how to do the research (see below) and, importantly, identified research areas where co-production could still genuinely happen at later stages in the study. In many areas, decisions have already been made and the research tools fixed (namely our questionnaires) and with these it is vitally important that we capture SURs reflections on using these and the issues which have been brought up, both for themselves and by service users, in order to present a balanced picture of what has and hasn’t worked at the point of dissemination.

Joint ownership of key decisions

Various areas and topics requiring decisions are taken to LEAP meetings. For example, we held workshops with both the LEAP and SUR teams to input into the statistical analysis plan. Trial statisticians presented and explained the analyses that usually take place in a trial, identified parts of the analyses where there was opportunity to shape the questions we asked and worked with LEAP members and SURs to identify and refine research questions (e.g. identifying sub groups of our participants who might experience peer support differently). There has been a variety of input into the literature review, principles, intervention development and fidelity index development.

A commitment to relationship building

Relationships between those on the co-applicant team have developed over time and on previous projects. This project has benefitted from and sought to build on these existing relationships.

The PPI co-leads set aside time with new SURs and LEAP members to make sure we can support them in ways which work for them, such as additional briefing before LEAP meetings or one-to-one meetings if a LEAP member cannot attend a meeting they would like to contribute to. The reflective spaces described elsewhere not only offer an opportunity to learn from experiences but to further foster relationship building within the team. This is particularly helpful to the researchers based away from the main study site. There is a continual need for spaces to be created for relationship building which is frequently challenged by time constraints. While time was costed in the funding bid for our PPI co-leads to do this work we have found that this was insufficient and have had to ‘borrow’ time from other parts of their role to be able to provide some of this support. We would certainly request more time for this from funders in future applications.

Opportunities for personal growth and development

It is important to establish and provide training and support needs, particularly to those with lived experience who may not have knowledge of specific areas (for example: trial methodology) or conversely, those who have research experience but have not previously been in a role where they are asked to explicitly share their lived experience. This has been a real challenge for those of us who have joined the study at a later stage, just to work on the full trial. A number of us have highlighted that there is not much space to meaningfully feed in our lived experience, which is why particular thought has been given to us feeding into qualitative schedules and the analysis plan. But, independently of this, capturing our reflections – and writing this up separately – does seem very important.

The PPI co-lead roles were created to provide on-going support and training for the SUR team, and we support opportunities for the team to attend and present at conferences as well as contribute to and lead on writing up the research for publication. At the SUR researcher team’s request, we have introduced additional workshop time to reflect on our experiences of co-production as well as time for the team to prepare publications exploring the learning from our project, both for them personally and for us as a team. We have agreed to continue to have meetings such as this whenever a particular piece of work which lends itself to being co-produced arises.

Flexibility

There is less flexibility in trial methodology, certainly compared to qualitative research and also compared to some of the mixed methods studies we have undertaken in the past, and this is a continuous challenge. The research questions asked are standardised and there is a protocol that has to be rigidly stuck to. Where there is flexibility, efforts are made to provide lived experience/other input to intervention development; fidelity index, process evaluation and the trial statistical analysis plan.

Continuous reflection

We have previously had six weekly reflective SUR team meetings. The PPI co-leads have also had individual meetings with the SURs every six weeks where SURs have wanted these. As yet no whole team reflection spaces exist but we are intending to begin reflective practice groups with an external supervisor for SURs to be able to regularly meet as a wider team to discuss the work, share learning and support one another. Something that a number of the SURs have felt is particularly important is having a document (a ‘reflective log’) to record all of our reflections. For example, experiences which have been uncomfortable in our role (in terms of being a researcher working from lived experience using fixed questionnaires) on the wards, feedback from our participants about the research, particularly what they would change, and reflections on what we could have done differently in hindsight (had there been more time built in earlier in the study). However, getting this up and running was delayed mainly because time had to be taken to develop a consensus as to how this document would be used and to develop a system to ensure contributions could remain anonymous. We are now at the point where we can all, anonymously, feed into this document.

Valuing and evaluating the impact of co-producing research

We have a ‘reflective log’ as well as monthly co-production meetings where we discuss and plan how to use our lived experience in the research. Members of the SUR team use the log to record their experiences of using their lived experience in the trial, both where they felt this was rewarding and might have had an impact, and where this was difficult to do. We have a commitment to writing up and communicating our experiences of working together and how this has impacted on research process and findings. We presented at the Research and Recovery Network conference in May 2018 about many of these challenges and how we are seeking to overcome them, as a way of disseminating knowledge about research co-production.

Key challenge: Co-producing a randomised control panel

If you are thinking of using a co-production approach in a randomised controlled trial there are a whole raft of additional challenges because of the strict methodology and because power over certain decisions generally sits with methodologists. It is important that SURs, LEAP members and other people contributing to the research from a lived experience perspective are aware from the outset where there is room for flexibility and where aspects of the research will be very standardised, and why. As a result of this rigidity it seems that there is a phase of the trial – the data collection – where co-production is largely dormant because the trial protocol, once agreed, is largely set in stone and cannot be deviated from (although there have been instances where minor revisions have been made, for example the window of time for follow-up interviews was lengthened.) This is done to ensure that there is a fair trial and that the research team cannot unduly influence the findings. This is why it is vital that experiential knowledge informs development of the trial at the beginning, including decisions about what is measured, why and how, and not just those aspects of the trial that lend themselves to co-production (e.g. developing the intervention, qualitative interviewing etc.).

There is also a later phase of the trial where we hope experiential knowledge will play a key role, and that is interpretation of findings. Statisticians will tell us which results are significant but making sense of those findings and the implication for them should, once again, bring together and explore different interpretations that might be informed by experiential, as well as academic and clinical knowledge.

Key benefit of co-producing your research: Improved and more relevant research

Co-production enables all voices to be heard and to contribute. Co-production not only delivers better, more relevant research, it aids buy-in from many different perspectives, which will hopefully make the research more relevant to the wider community including practitioners, academics, managers and commissioners of services.

A vast amount of lived experience of doing peer support went into developing the handbook and training for peer workers, and into the principles framework on which the study is based. While we are exploring this in detail in the trial, observations by the SUR team suggest that, by and large, there is a high degree of adherence to the principles in the way the peer support is being delivered at study sites. This is really important to us as reviews of a number of previous trials have suggested that it hasn’t been clear how what peers have delivered is different to other forms of mental health support (with study findings reflecting that). Co-producing the peer support was a major part of our strategy to address this challenge. For us this was all about ensuring that experience-based knowledge, as well as academic knowledge, informed that process. So, we did review existing research on peer support, and we did involve psychologists on the team in thinking about how change happens for people, but the experiences of people directly involved in doing peer support was crucial.

Five key learning points:

- Make sure that there is as much experiential knowledge in the early stages of developing the research as possible and develop clear processes or methods that enable people to shape the way the research is done and also reflect on how – and how much of – the research is being co-produced.

- Be open with the whole team about your aspirations for co-production – some people won’t be familiar with the idea – so that the team can learn to work through dialogue from the start.

- Extra time and resources must be factored in for genuine co-production to happen. Identify and build in spaces for flexibility in advance, or where flexibility isn’t possible, make sure everyone knows what to expect.

- Inform people of how their contributions are shaping the research/what changes have been made so that people feel their contributions have been valued.

- Outline when and where key decisions will be made and ensure that those who will be included in the decision have time in advance to prepare for and contribute to these decisions.

Glossary:

ENRICH Peer Workers are people with previous experience of using mental health services who are employed, trained and supported to use those experiences to support others during the discharge (from inpatient care) process.

ENRICH Peer Worker Coordinators are the main point of contact at each site. Involved in the development and piloting of the ENRICH peer support for discharge handbook. Team lead for the peer workers on their site, initially leading on the recruitment and training of the team (including the Local Advisory Groups – see below) and then supporting and supervising the team as they provide peer support on the wards and in the community. Ideally have experience of working in mental health services from a lived experience perspective and experience of delivering mental health care in a clinical context.

National Expert Panel: (NEP). This was a group which met twice during the autumn of 2015 with the specific task of helping to coproduce the Peer Support Package with the ENRICH research team. All members of this group (approximately 10 people) had lived experience of various aspects of peer support in mental health.

Local Advisory Group: (LAG). Local Advisory Groups (between 6 and 12 in each) were set up at each site to bring expertise to the design and development of the ENRICH intervention and to inform the research team about what would work best in terms of implementing the peer support intervention in local services. LAGs are mixed groups of lived experience experts and local stakeholders with a demonstrated commitment to peer support and meet at various stages of the study.

LEAP: (Lived Experience Advisory Panel). A group of 10 people with lived and/or caregiver experience to advise on key decisions and also to support the lived experience/service user researchers on the teams. The group meets approximately twice a year throughout the study and includes perspectives from both the statutory and voluntary sectors.

Useful references for co-producing research:

Some of our own work around co-production/involvement:

Steve Gillard, Rhiannon Foster, Kati Turner (2016). Evaluating the Prosper peer-led peer support network: a participatory, coproduced evaluation. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 2016, 20:2, 80-91

Gillard S, Foster R, Papoulias K (2016) Patient and public involvement and the implementation of research into practice. Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 11 (4): 256-267

Steve Gillard, Kati Turner, Sarah Gibson (2014). Balancing good research with good mental health: A step-by-step guide to employing and supporting service user researchers. Section of Mental Health, St George’s, University of London,

Appendix to: Good practice guidance for the recruitment and involvement of service user and carer researchers. NIHR, Clinical Research Network, Mental Health.

Gillard S, Simons L, Turner K, Lucock M, Edwards C (2012) Patient and Public Involvement in the Co-production of Knowledge: Reflection on the Analysis of Qualitative Data in a Mental Health Study. Qualitative Health Research, 22(8): 1126-1137

Gillard S, Borschmann R, Turner K, Goodrich-Purnell N, Lovell K, Chambers M (2011) Producing different analytical narratives, coproducing integrated analytical narrative: a qualitative study of UK detained mental health patient experiences involving service user researchers. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 15(3): 239-254

Gillard S, Borschmann R, Turner K, Goodrich-Purnell N, Lovell K, Chambers M (2010) ‘What difference does it make?’ Finding evidence of the impact of mental health service user researchers on research into the experiences of detained psychiatric patients. Health Expectations

Kati Turner and Steve Gillard (2011). Still out there? Is the service user voice becoming lost as user involvement in mental health research moves into the university?. Critical Perspectives on User Involvement (Chapter 15), edited by Marian Barnes and Phil Cotterell, Policy Press

Steve Gillard, Kati Turner, Kathleen Lovell, Kingsley Norton, Tom Clarke, Rachael Additcott, Gerry McGivern, Ewan Ferlie (2010)

Staying Native: Co-production in Mental Health Services Research. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 23(6): 567-577

Steve Gillard, Kati Turner, Marion Neffgen, Ian Griggs, Alexia Demetriou (2010). Doing research together: bringing down barriers through the ‘coproduction’ of personality disorder research. Mental Health Review Journal, 15(4): 29–35

The ‘Ideal’ Ward Round

James Shutt, My Rights

Organisations involved in the research:

University of Nottingham, Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, My Rights, POhWER,

Summary of the research:

‘The Ideal Ward Round’ is a health research project led by people with lived experience of care and treatment in adult in-patient mental health services. The project was co-produced with carers, advocates, mental health professionals and academic researchers. The project aimed to:

- establish the views of patients, carers and professionals on: the role of, experience of and ways of improving ward rounds – in the context of acute adult in-patient mental health services, within one NHS Trust in England develop a set of recommendations that would lead to improvement in ward round processes, outcomes and experiences for those who attend ward rounds, particularly for patients.

Patients, carers and staff have historically reported negative experiences of ward rounds in acute adult mental services. Yet there remains limited evidence of the nature and extent of these negative experiences and an absence of reported views from ward round participants, most notably from patients themselves, as to how improvements to the overall experience of ward rounds could be made or how specific problems with the ward round experience could be identified and addressed.

As a project initiated by people with lived experience of care and treatment within adult in-patient mental health services and involving a number of key stakeholder groups, ‘The Ideal Ward Round’ project adopted a ‘Participatory Action Research’ (PAR) approach to researching the experience of ward rounds. The PAR approach emphasises collaborative participation of professional researchers and stakeholder communities in the creation of knowledge on research questions raised by and directly relevant to the stakeholder community. Usually driven by the stakeholder community, PAR projects offer a democratic model of knowledge-creation by research focusing on a cycle of planning, action, observation and reflection, with shared decision-making and collaboration at each stage. PAR itself as an approach emphasises shared control over the research process rather than a specific research methodology.

Utilising a PAR approach, the stakeholder community become research partners in the knowledge-creation process rather than simply being research subjects, with the intention that the research process increases the community’s capacity to solve its own problems without the need for outside ‘help’. Knowledge-creation about the ward round experience therefore becomes research with rather than research about mental health service users, the community determining the questions the research will consider, the methodology to be employed and holding the research accountable in terms of its level of impact. In this way, a PAR approach makes the research process implicitly empowering or ‘emancipatory’ in nature, particularly to those individuals who view mental health care and treatment as first and foremost involuntary and disempowering. In emphasising action as essential and consequent to the research process, PAR implies an intervention and change to the status quo further signifying greater, more widespread change toward the aspirations held by the stakeholder group. In this case, this means mental health service users having greater involvement, influence and ultimate control of their immediate care and treatment decisions and in the long-term greater freedom to determine the meaning and self-management of their mental health experiences.

‘The Ideal Ward Round’ project undertook a survey of almost 100 respondents including current in-patients, people who had received treatment or care in in-patient services within the last 12 months, and carers of both groups. Professionals included health care assistants, nurses, occupational therapists, psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers. Total responses showed a range of positive-negative experiences across and sometimes within groups of respondents. Responses provided a number of challenges to the ways that ward rounds are currently managed, suggesting improvements are needed regarding the practical arrangements for ward rounds, ownership and management of ward rounds and the involvement of patients and carers in ward rounds, particularly in clinical decision-making. Based upon the responses and a series of further focus groups comprising people with lived experience, carers and professionals, the project developed twelve recommendations for ward rounds in adult in-patient mental health services. These were piloted on three acute in-patient wards in one NHS Trust with evaluations being undertaken by members of ‘The Ideal Ward Round’ project group. These evaluations evidenced an overall improvement in experience for in-patients and others. During the research process, PAR itself became an important means of articulating and directing the co-produced nature of the research.

Find out more about ‘The Ideal Ward Round’

How did the key principles of co-producing research find expression in your research?

‘The Ideal Ward Round’ project was established by a group of volunteers with experience of in-patient mental health services at Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust’s Involvement Centre together with Involvement Centre staff, mental health professionals from the Trust and representatives from local advocacy services.

From the initial idea the project was framed as a partnership between people with lived experience of mental health services, carers of people with lived experience, mental health professionals and academic researchers. The group acknowledged that the research needed guidance from professional researchers, however the group did not want to ‘hand over’ the work to researchers, but to be directly part of acquiring knowledge as a process of empowerment in itself. The group had noted from the previous research about experiences of ward rounds, the common role that power imbalances between patients and professionals seemed to play. Also, the absence of carer views in the existing research and the limited range of views from different mental health professionals, was itself an impetus for co-producing research with carers and people from different mental health professions. The impetus to share power initially came from the group’s view that significant problems existed in ward rounds due to a fundamental imbalance of power embedded in the culture of mental health services and that any serious attempt to investigate this culture critically would necessarily require a research environment of power sharing and joint ownership that included all perspectives and skills. This power sharing and inclusion of all perspectives and skills was achieved by:

- establishing three rules for everyone involved in the project from the beginning:

- everyone’s opinion holds the same weight

- wherever we go in terms of methodology or outcomes, we decide together

- whatever the project ultimately turns out to be, it has to make a real difference, especially for patients / people with lived experience.

- holding regular project meetings at the Involvement Centre for all members of the project to attend, taking the format of a chaired meeting with an agenda but with an open forum where ideas and developments at each stage of the research project could be discussed and agreed by a common vote.

- chairing meetings effectively in order to establish a balance of views and participation.

- seeking to manage ‘knowledge claims’ between project members by a principle of parity of knowledge (e.g. between clinical knowledge and knowledge of mental distress by experience) in order to prevent the owner of one type of knowledge dominating.

- prioritising shared ownership of the project, particularly of owning the data collection and analysis stages of the project.

- supporting members including those with lived experience, carers and advocates with limited/no prior research experience to be fully involved in undertaking interviews and gathering and analysing data.

- establishing sub-project teams for each stage of the research with a representative of each group (i.e. those with lived experience, carers, advocates, mental health professionals) wherever possible.

- facilitating focus groups with equal representation of the different stakeholder groups to work together to finalise the twelve recommendations for ward rounds.

The format of discussions in project meetings, including focusing on sharing personal experiences of ward rounds from different perspectives, fostered a continual reflective process among the project team, leading more and more to a respecting and valuing of the knowledge of everyone involved in the research project. This respecting and valuing of people’s knowledge as well as reciprocity was particularly realised through the process of joint knowledge creation, with project members actively working together and sharing the processes of interviewing, data collection and data analysis with everyone’s contribution acknowledged and valued. Academic researcher members worked directly with members with lived experience in order to share knowledge and develop skills regarding data collection and analysis. In return, members with lived experience advised and supported how best to engage with in-patient respondents, and helped to achieve better interactions during the interview process. Mental health professional members reported significant benefit of being involved in the project in terms of gaining deeper insight into the experiences of patients and carers and feeling more empowered to challenge prevailing cultures in mental health services.

Building and maintaining relationships

The ’Ideal Ward Round’ developed out of an existing relationship between advocacy services and Nottinghamshire Trust’s Involvement Centre, where patients, carers and advocates’ views had been shared in a regular service user forum. The members of this forum were already clear in their role as representing more broadly the views of patients, carers and advocates. The Involvement Centre encouraged the involvement of professionals at all levels of the Trust in order to link service user and public concerns to service development. The environment in which the idea of the ‘The Ideal Ward Round’ could develop naturally therefore already existed to some degree. However, the project entailed establishing new relationships with mental health professionals as well as professional researchers. Interest in the project developed quickly, with professionals in the Trust with research experience and researcher practitioners from the University of Nottingham joining the project group . Their roles within the project group as advisors on the research process developed into sharing their expertise and helping other members to develop research skills as part of project sub-groups. Relationships developed within the project sub-groups were extremely important. Within the sub-groups, members were allocated specific roles and tasks, such as interviewers and ward leads. The process of members supporting others to take on new roles and to undertake the research as a co-ordinated group galvanised these relationships and renewed commitment to the project as a whole. Improving the confidence of members to engage in project decision-making and to share accountability for the development of the project was an important part of building and maintaining relationships, particularly with members with lived experience and carer members.

‘The Ideal Ward Round’ did involve initial challenges to the building and maintaining of relationships amongst its project team. The context of ward round experiences in mental health services is itself prone to perceived and real power imbalances, mainly between patients and mental health professionals,. In the early stages of the project this had to be acknowledged, as people’s personal experiences, resonating with powerful feelings such as hurt and anger about what had happened to them in ward rounds, jarred against professionals’ reflections on issues such as ward pressures, managing patient risk and the difficulties of challenging existing workplace practices. Carers also raised the challenge of them understanding ward processes and not being kept informed by professionals. Debates could be heated, yet everyone in the room was clear that they were there because they believed something wrong in these processes needed to be talked about openly and changed, and that everyone else in the room should be part of that change. This shared commitment (along with the three rules noted above) was important at this stage, as was effective chairing of the project meetings and the balancing of views about the problems of ward rounds in the early stages. The Trust’s Experience Lead, who managed the Involvement Centre and had established relationships with most project members, was able to chair in a sensitive and balanced way that was fair to all members and managed conflict effectively.

At the start of the project, a number of those with lived experience and carer members expressed a lack of belief in the viability of the project to be truly co-produced. They believed that at some point they would become side-lined or the project shelved by powers beyond them. This view changed as relationships developed between the project team and the aims of the project became realised over time.

The project also benefited from stakeholders (viewed sometimes as ‘informal’ members) with an interest in the aims of the project who offered to do what they could to support and promote the project. For example, one of the Trust’s clinical directors, although unable to commit to becoming a member of the project team, supported awareness of the project at multiple levels in the Trust and beyond, also attending some project meetings in order to show this support. A relationship with the Collaborating Centre for Values-based Practice in Health and Social Care at the University of Oxford also provided additional interest in and desire to share the outcomes of the project and gave members increased impetus to realise the project.

How did the key features of co-producing research find expression in your research?

In addition to the ‘unwritten’ rules and the principle of parity between different types of knowledge held by different members of the project team, from the outset, the ground rules established for project meetings included:

- being respectful of other member’s opinions and experiences during discussions

- a minimising of the use of technical terms and jargon, or otherwise explaining terms when they could not be avoided

- a commitment to try to gain each member’s views in pre-decision-making periods of discussion

The Involvement Centre forum had already established an open, ‘horizontally’ structured environment where these ground rules could be agreed easily, and where ongoing dialogue between people with lived experience, carers, advocates, professionals and researchers could take place within a ‘neutral’ space. The project was very much born of and developed from ongoing dialogue between its members, from a group of mental health service ‘users’ and advocates initiating the idea. This led to discussions at the Centre with interested professionals and researcher stakeholders, and then onto the development of the research idea and process and setting out the work that would need to be done and the roles to be allocated at each stage.

Continuous reflection was also very important for the process of the project as a whole and for maintaining the relationships within the project team. The exchanging of views on ward round experiences, mentioned above, established a reflective discourse between members that developed into a reflection on the research process itself at each stage. The Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach taken by the project group also ensured a continuous cycle of planning, action, observation and reflection for the purpose of considering each stage of the research process and the impact of it on subsequent stages. Tasks were allocated to project subgroups at each stage and on a monthly basis there was dialogue between the project group as a whole and the subgroup teams. This ongoing dialogue was important in maintaining communication and inclusion of project member’s views and preventing potential shifts in ownership of the project, particularly to those working within the sub-groups.

It also encouraged joint ownership of key decisions on a practical level so that while project sub-groups could effectively make decisions within themselves, wider project decisions and larger conceptual or methodological discussions and decisions around the research were reserved for face-to-face meetings, where information was presented, ideas discussed and decisions put to a vote. Knowledge sharing among members, particularly research methodologies and practice shared by professional researcher members, also encouraged other members to take ownership of key decisions regarding the research process, such as determining sample sizes of the different survey groups.

The iterative nature of this action research approach also guaranteed greater flexibility as the team were able to reflect and develop a response to findings from each stage of the project. For example, it was only at the stage of having analysed the survey data that the project team agreed that focus groups were a key step in the research process. These focus groups ensured that the recommendations from the research could be discussed within mixed cohorts of people representing the different groups of respondents surveyed.

The commitment to relationship building already discussed did not just take place within the project team. It also included seeking support by and participation from different teams and wards within the Trust, wider networks such as the Institute of Mental Health and Recovery College, as well as community and third sector organisations, such as local advocacy and ‘service user’ led organisations. Direct engagement by members of the project team was important in developing these relationships, which allowed stakeholders to see the team’s commitment to the process and the outcomes of the project and to making real changes for people with lived experience. Direct stakeholder engagement became an opportunity for personal growth and development, as members of the project team with lived experience had the opportunity to deliver seminars and presentations about the project.

Delivering these seminars and presentations was important as an opportunity for growth and development as well as a key way of valuing and evaluating the impact of co-producing the research. For members, including those with lived experience and carers, presenting the findings of the research and acting as representatives of an action research project has been a key way of taking ownership of the research.

Key challenge: Time and resources

The commitment of time and energy to a co-produced project is something that all members of the project group underestimated. The best way of addressing it is by being honest about the time and resource commitments that the project’s scale, ambitions, membership, approach to inclusion, flexibility and reflection can accommodate. The positive aspect is that, if a project is genuinely co-produced, there will be more motivation for members or potential members to commit and contribute.

The certainty often required by funders, for example about timescales, outcomes and the overall life cycle of a research project can be challenged by the principles, features and real-life experience of co-production. Those funding research therefore may be deeply troubled by the prospect of embracing these aspects of co-produced research! However, those involved in co-produced research need to speak loudly about the benefits of producing research, particularly in terms of collaborative service improvement, knowledge exchange, relationship building between services and communities and capacity building within communities.

Key benefit of co-producing research: Power sharing and parity of views between mental health service users, carers and mental health professionals

Giving a voice to an under-represented group in health / social research, i.e. people who experience mental health problems, and increasing the capacity of this group to undertake valid research and engage effectively in debates about service provision. Our work ensured that mental health service users were involved in developing recommendations for mental health service improvements.

The development of positive relationships between project members that positively challenges existing perceptions of mental health service ‘users’ in a passive ‘sick’ role and professionals in an active paternalistic role.

Five key learning points:

- Establish what ‘co-production’ means in practical terms for you and the members of the project;

- Set out how the project will be accessible to people not from professional or academic backgrounds; and what support will be given to members to involve them as much as possible, should they have difficulty being involved.

- Agree basic ground rules at the start of the project. This should cover inclusion, decision-making, ownership and accountability, and how you will work together.

- Meet regularly throughout the project life cycle and try to put major decisions to a group vote wherever possible.

- Acknowledge everyone’s contribution and make sure credit is shared equitably.

Useful references for co-producing research:

Gemma Stacey, Anne Felton, Alastair Morgan, Theo Stickley, Martin Willis, Bob Diamond, Philip Houghton, Beverley Johnson & John Dumenya (2016) A critical narrative analysis of shared decision-making in acute inpatient mental health care. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30(1): 35-41

Co-producing the research agenda for mild-to-moderate hearing loss in adults: A James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership

Jean Straus and Robin Wickes, Patient Advocates

Helen Henshaw, Senior Research Fellow, NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre and NIHR Career Development Fellow, University of Nottingham

Organisations involved in the research:

James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership Steering Group (patients, clinicians, professional bodies and third sector organisations):

- James Lind Alliance (David Crowe, Advisor and Steering Group Chair)

- Hearing Link (Linda Sharkey, Audiologist and User-Organisation Advocate)

- Patient advocates (Jean Straus & Robin Wickes)

- NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre (Helen Henshaw, Senior Research Fellow and Priority Setting Partnership Coordinator; Melanie Ferguson, Associate Professor, Research Lead (mild to moderate hearing loss), and Consultant Clinical Scientist (Audiology)).

- British Society of Hearing Aid Audiologists (Barry Downes, Audiologist)

- British Society of Audiology (Helen Pryce, Speech Therapist)

- British Academy of Audiology (Vinaya Manchaiah / Sue Falkingham, Audiologist)

- ENT (Natalie Bohm, Ear Nose & Throat (ENT) Surgeon)

- Cochrane UK (Sarah Chapman, Knowledge Broker)

Wider stakeholder groups:

- People with mild to moderate hearing loss, patients, and their family, friends & clinicians

Figure 1: Steering group members at the British Academy of Audiology annual conference, 2014 (left to right): Melanie Ferguson, Barry Downes, Helen Pryce, Helen Henshaw, Linda Sharkey, Vinaya Manchaiah.

Summary of the research:

Hearing loss affects 12 million people in the UK, with the majority (92%) experiencing mild-to-moderate hearing loss. It is a highly prevalent chronic long-term condition that is costly to society. However, the greatest cost is for individuals experiencing hearing loss who face challenges in communication, which can lead to reductions in psychological wellbeing, quality of life, and economic independence.

All too often, research on the effects of treatments for conditions overlooks the priorities of those affected by the condition. The James Lind Alliance (JLA) priority setting partnerships (PSPs) are pioneering in:

- bringing together patients, carers and clinicians on an equal footing

- identifying treatment uncertainties that are important to those groups

- working together to jointly identify and prioritise treatment uncertainties

- producing a ‘top 10’ list of jointly agreed priority research questions to be presented to funders

From July 2014 to September 2015, we undertook a JLA PSP for mild-to-moderate hearing loss in adults. Coordinated and led by patients, clinicians and their advocates, the PSP consisted of four key stages:

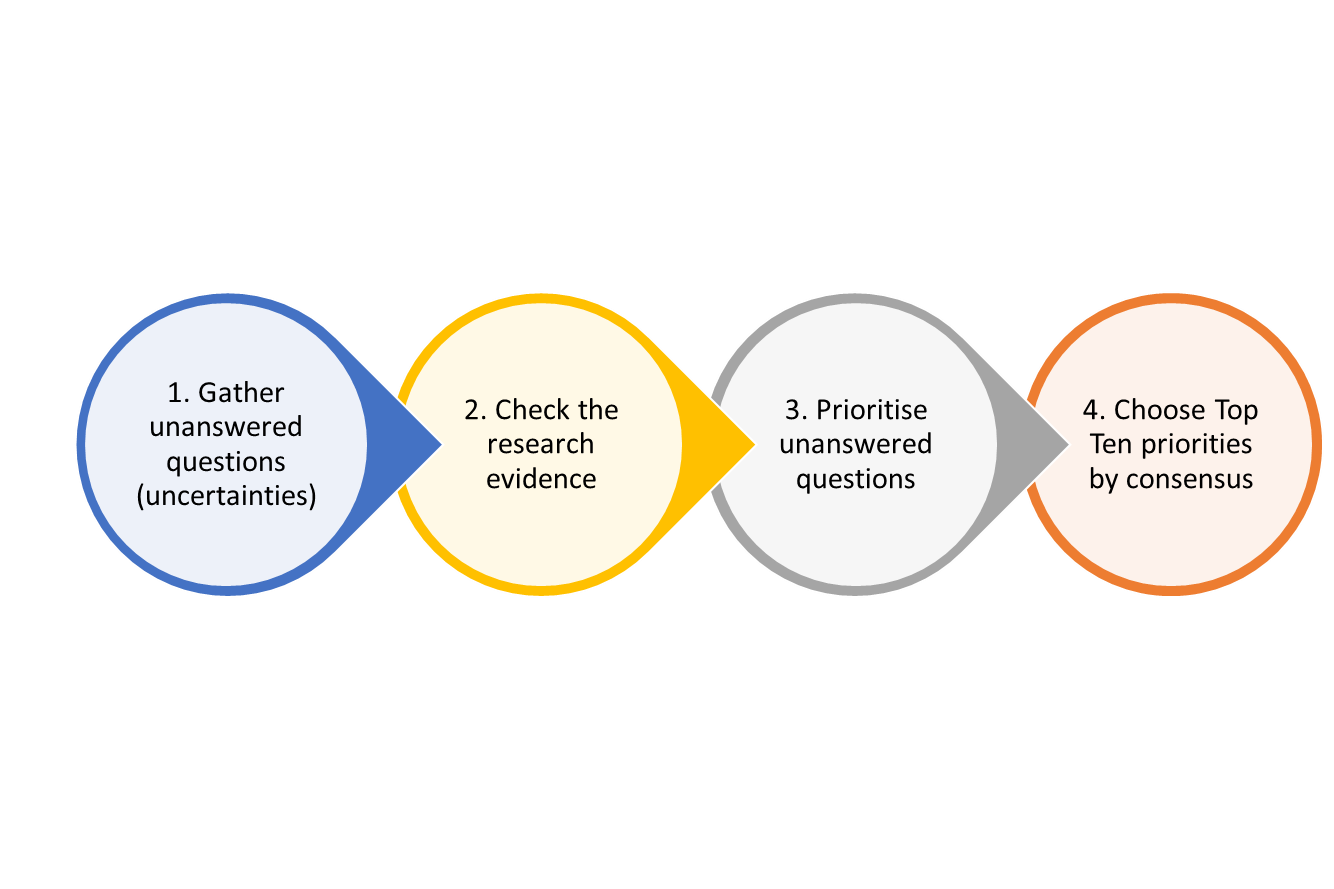

Figure 2: A diagram showing the James Lind Alliance (JLA) method: 1) Gather unanswered questions (uncertainties) 2) Check the research evidence 3) Prioritise unanswered questions 4) Choose Top Ten priorities by consensus

The four priority setting partnership steps:

- An initial survey of patients, their friends and family, and clinicians was used to gather unanswered questions about the diagnosis, treatment and management of mild to moderate hearing loss in adults. We received 1,147 questions in total, submitted by 461 individual respondents.

- Indicative (overarching) questions were generated by the Priority Setting Partnership steering group, by collating the individual questions into common themes. These indicative questions were then checked against the existing research literature to ensure they were ‘true’ uncertainties.

- An interim survey of patients, their friends and family, and clinicians asked respondents to rank 87 indicative unanswered questions in terms of their priority for research (from ‘not a priority’ to ‘very high priority’). We received rankings from 486 individual respondents.

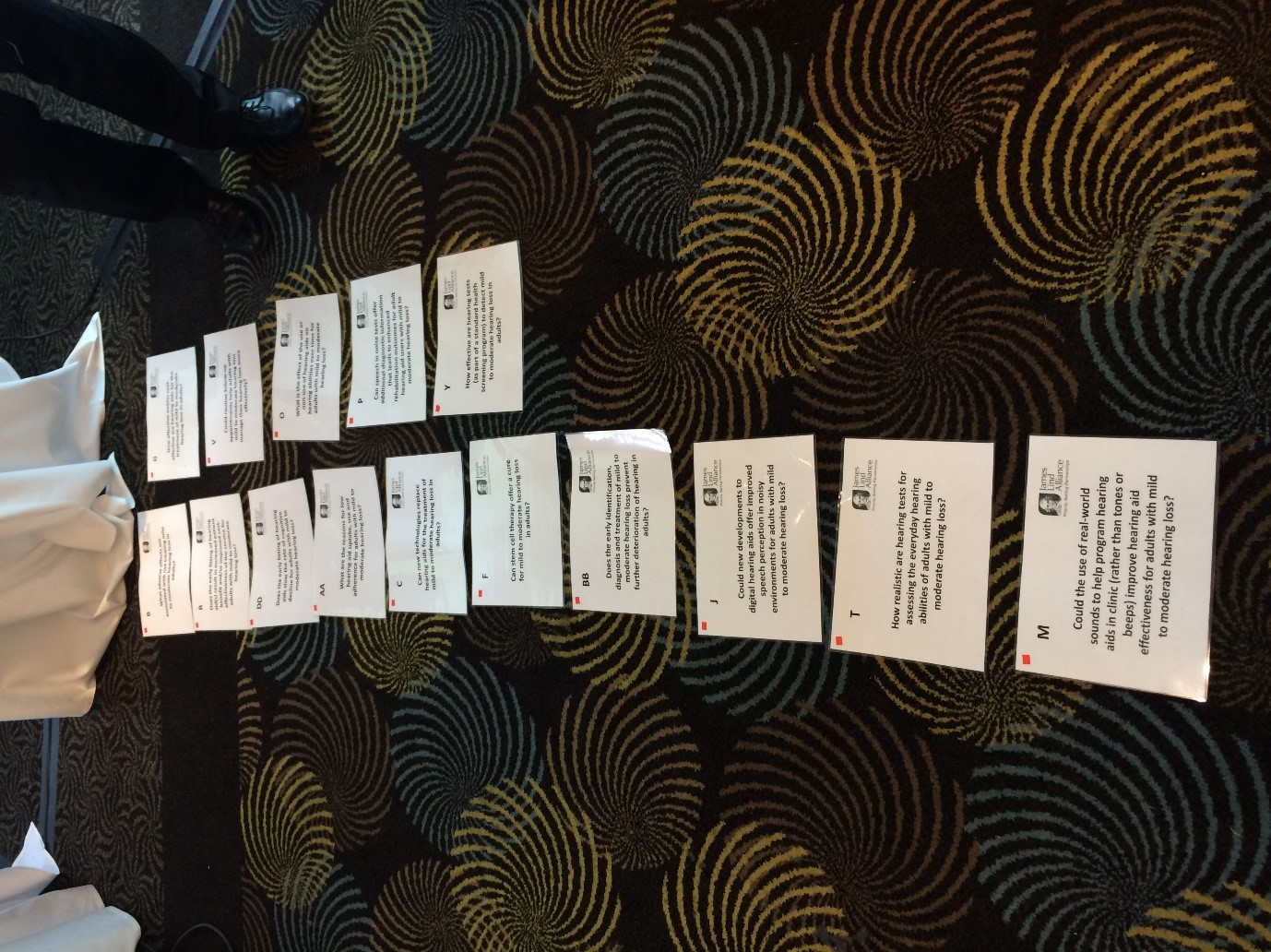

- A final full-day prioritisation workshop of patients, their family, friends, and clinicians was held to agree the top 10 priority unanswered questions for research by consensus.

Co-production was integral to the formation, development, leadership, management, inputs and outputs of the JLA PSP.

The final workshop used an inclusive decision-making approach called nominal group technique, a well-established approach to decision making whereby everyone’s opinions are taken into account. Within this technique, each participant reviews the questions and gives their personal view about their priority order, before undertaking a shared (group) ranking exercise. This is then followed by small group discussions and a second round of ranking. The ranked orders for each question per contributor is then summed to identify the top 10 overall priority questions.

The top 10 priority questions for research in mild to moderate hearing loss in adults were published in 2015 within a co-produced article in the scientific journal, The Lancet.

Links to the research:

JLA mild-to-moderate hearing loss PSP webpage

Evidently Cochrane blog #1: Priority setting in research: what do you want to know about hearing loss?

Evidently Cochrane blog #2: Top 10 priorities for research on mild-moderate hearing loss.

The Lancet, top 10 research priorities for research in mild-to-moderate hearing loss in adults:

How did the principles of co-producing research find expression in your research?

Sharing of power

Health research is often driven by researchers and policy makers, with little reference or acknowledgement of the needs and wishes of those who will be directly affected by the outcomes. This JLA PSP grew from a desire to change how hearing healthcare research is prioritised, which came from both the coordinating team at the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre and the user-organisation Hearing Link (a leading UK charity for people with hearing loss, their families and friends). Hearing Link identified two patient advocates, Jean Straus and Robin Wickes, both of whom had lived-experience of hearing loss and were instrumental in shaping the PSP from start to finish as members of the PSP team. The role of the patient advocates was to ensure that the priority setting process remained grounded in the patients’ experiences and that the outputs were relevant and aligned to patients’ needs. They worked side-by-side with other team members (for example audiologists, hearing therapists and their advocates), and had equal say in the running of the PSP including decision making. Both Jean and Robin reported feeling fully involved in all the steps of the priority setting process.

“In my view the single most effective contributor to the success of the project was teamwork. Every person on the Steering Group was made to feel an equally important member of a single team with an equally important role to play. Everyone’s views were always sought and respected. And responsibility for setting the project’s strategy and making the key decisions were shared on an equal basis. As a consequence, not only did the project yield high quality results; it was also a pleasure to be involved in, with morale and energy kept at a high level at all times. It was an excellent example of the old adage about the whole (project team) being greater than the sum of its parts.” Robin

“It was sometimes down to me to be bold and even interrupt proceedings if I could not hear or did not understand. Otherwise, I would not have been effective.” Jean

Including all perspectives and skills

In partnership with Hearing Link, a successful application for funding to the Nottingham University Hospitals Charity was co-developed, and the partnership was expanded into a steering group representative of the most diverse range of stakeholder groups and organisations we could collectively generate. As a team, we patients, clinicians and researchers worked together to identify a broad range of key stakeholders relevant to the Priority Setting Process. We looked to include representatives whose views might vary, such as private and NHS professionals. We also understood there might be researchers or clinicians involved who were unaccustomed to simplifying scientific or clinical concepts for lay members. Care was taken to ensure any instances of this were identified and actively managed as part of the Priority Setting Process. We took on board and dealt with the inevitable frictions, knowing we were creating richer discussions and actively generating learning throughout.

“Inclusivity was an important criterion in deciding who to send the surveys to. We wanted to make sure that the responses were from as broad a cross-section as possible of the relevant community. As well as sending the surveys to the large network deaf contacts that I have developed through my volunteering activities with Hearing Link and Action on Hearing Loss, I also sent them to the Head Offices of Age UK, Probus and the University of the Third Age for onward distribution to their contacts and members. Then I searched the internet for other deaf groups and highlighted in particular groups of deaf people from ethnic minorities to send the surveys to.“ Robin

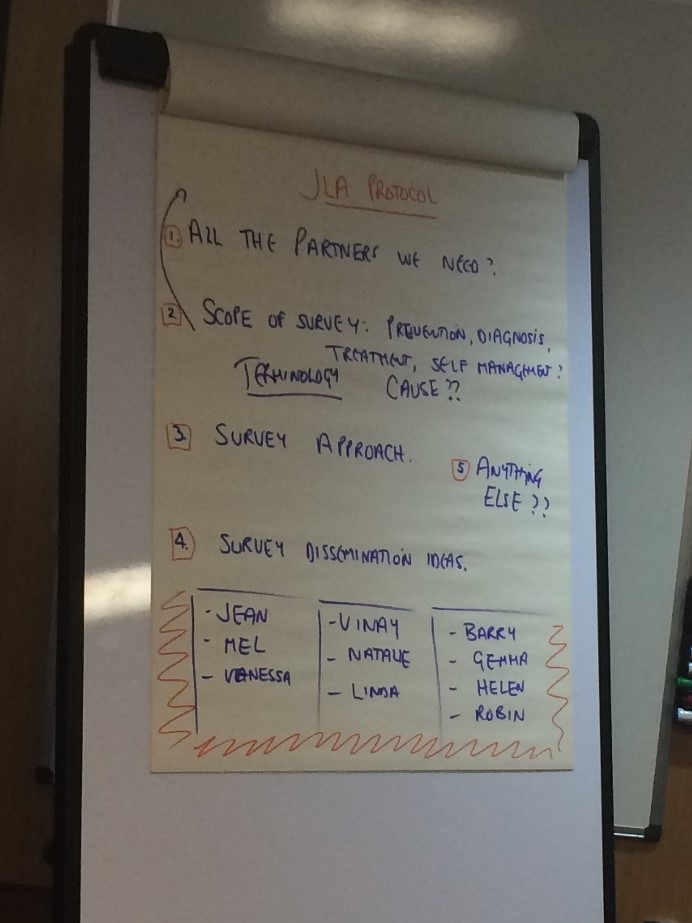

Figure 3: Co-defining the JLA PSP protocol with patients, researchers and clinicians.

Building and maintaining relationships

Steering group members took responsibility to expand the PSP by collectively reaching out to their established personal, social and professional networks using promotional materials, such as email banners, editorial articles and flyers, which were co-designed as a team. These routes were then formalised in the co-production of a communications plan, which was used to elicit responses to the stage 1 and stage 2 JLA PSP surveys.

“The way that the project was structured and managed made it very easy as well as necessary to build relationships. Our regular Steering Group meetings took place in Nottingham and were several hours long, with plenty of opportunities before and after the meetings as well as during breaks to talk with other members both about our backgrounds and about the project itself. Because we were such a diverse group brought together by the common theme of hearing loss and reliant on each other for making the project a success, we were all eager to get to know each other, compare notes about the project and draw on each other’s experience and expertise. Working relationships grew stronger as the project progressed and were particularly valuable when the going got tough, for example when we were breaking down and categorising the large number of responses to our first survey.” Robin

Figure 4: Co-produced promotional materials were developed to promote the PSP and encourage participation in surveys

Reciprocity

All of the work undertaken at the NIHR Nottingham Biomedical Research Centre is developed with and for patients and members of the public. We aim to address real-world problems, and in turn, we can inform novel solutions to help people with hearing loss better manage, adapt and engage in everyday life. The pinnacle of this approach is the James Lind Alliance PSP process, whereby people with everyday experience of hearing loss (either as a result of direct experience, familial association, or clinical exposure) can actively shape and prioritise future research priorities and influence which research questions attract future funding from research commissioners. In return, we benefit as researchers by gaining a deep understanding of the challenges faced by people with hearing loss. We are then better able to target our own research endeavours and conduct research that will make a real difference, and (importantly) secure research funds to help support this priority research.

“Through my work with the PSP, I met some of the top individuals in the fields dealing with hearing. I learned about processes in research that I would never have been privy to otherwise. Instead of being locked in, or out, with my hearing loss, I was involved and part of a dynamic energetic process wherein my hearing needs were well attended to as well.

Though the project itself consisted of a lot of terminology that wasn’t immediately obvious to the lay person like me, I came to respect that in order for any of my questions to be answered, rigorous scientific procedures had to be applied.

Enabling a lay person with lived experience of a condition, such as myself, to contribute to a project like this almost inevitably leads to opportunities for personal growth and development. My value as a participant has been rewarded in that I have been taken on in steering groups on tinnitus, dementia and hearing loss, and hearing loss in care homes, led by participants I met through this work. I’ve been invited to conferences by participants. In fact, I am now embedded in a world of scientists, NHS professionals, and patient advocates. I believe the experience gave me tools to evaluate and make decisions, and I have therefore been more useful as a ‘patient’. For us as the lay members of the research team, the public (patients, friends and family, carers, clinicians) gave us their vocabulary – their unanswered questions became our unanswered questions – and we interpreted it. Our own patient experience is validated, and we are empowered. Shared vocabularies are developed.” Jean

“I have personally reaped significant benefits from my involvement in the project. For many years I have been a keen volunteer for the charities Hearing Link and Action on Hearing Loss, with roles including providing face-to-face practical and emotional support to deaf people and delivering deaf awareness talks to a wide range of organisations. As a by-product of the PSP project, a great deal of new knowledge about all sorts of issues to do with hearing loss rubbed off on me from my association with the audiologists, academics and other specialists on the team. Ever since then I’ve been drawing on this new knowledge in my volunteering activities – for example talking about the possible linkages between deafness and cognitive issues.” Robin

Respecting and valuing the knowledge of all those working together on the research

“The James Lind Alliance priority setting partnership involved disparate groups, which came together with the same shared goal – identifying research priorities from the perspectives of those who had lived, shared or professional experience of mild to moderate hearing loss. What came out of the process was new knowledge. Our minds were stimulated to think beyond what we ‘knew’ because of the expertise and experience of the people we were working with.

For example, over and over again Robin and I expressed a desire for certain questions to be included in the questionnaire. We were taught about how research questions are structured, and so discovered that if a research question didn’t fit into a certain grammar, it couldn’t be researched according to the terms of the Priority Setting Partnerships. Learning these procedures was intellectually stimulating but also helped to take away some of the edge that we as patients sometimes feel, when we suspect we’re not being heard. It was reassuring that there were also clinicians with hearing loss participating in the research. As well, for me, to interact with people from disparate backgrounds and experiences was tremendous.

The project was an accumulation of shared knowledge, inspiring us to move forward in redefining what research for mild to moderate hearing loss should be about – answering the questions of those who experience it on personal or professional levels. Clinicians and researchers looked at Robin and me and changed the way they responded accordingly. For example, they learned which solutions enabled us to hear and process, and which did not. I think several were struck by the fact that you couldn’t simply sort hearing loss by having a hearing device or following inclusive procedures.

We found that by following strict JLA procedural guidelines, a discipline for all of us, we were obeying ground rules that eliminated any opportunities for experiencing hierarchy.” Jean

“In the same way that I learned a great deal about deafness from the audiologists, academics and scientists on the PSP team, these specialists were eager to learn from me about the practical and emotional issues associated with hearing loss – things like self-management techniques, communication challenges and the risks that people with hearing loss will become isolated and anxious and what can be done to mitigate these risks. The collaborative way that our team was managed was highly conducive to transferring skills and knowledge.” Robin

How did the key features of co-producing research find expression in your research?

Establishing ground rules

The steering group formed the core of the PSP. At the outset, they signed up to the JLA method (figure 2) and the JLA core principles, which are:

- Transparency of process

- Balanced inclusion of patient, carer and clinician interests and perspectives

- Exclusion of non-clinician researchers for voting purposes, although they may be involved and helpful in other aspects of the process

- Exclusion of groups/organisations that have significant competing or commercial interests, for example pharmaceutical companies

- Audit trail of original submitted uncertainties, to final prioritised list

- Priority setting only commencing after the uncertainties have been formally verified as unanswered

This enabled all members of the partnership to feel confident in expressing their views, concerns, opinions, and share their experiences – safe in the knowledge that this was of equal value to the views and opinions of the other members of the group. An independent facilitator from the JLA, David Crowe, with no knowledge or experience of mild to moderate hearing loss, chaired all Steering Group meetings in accordance with the JLA method. His role was to facilitate adherence to the JLA protocol throughout the PSP process, whilst ensuring that patients, carers and clinicians were able to work together on an equal footing.

We were particularly mindful of the communication challenges faced by PSP steering group members with hearing loss. As such, in addition to the JLA core principles which governed the PSP procedure, we also generated our own ground rules for good communication to ensure that all PSP steering group members were actively engaged at each stage of the PSP process.

To ensure inclusivity, equity and equality throughout the process, we:

- Held the majority of our steering group meetings face-to-face

- Utilised speech-to-text (real-time) communication support.

- Briefed all steering group members on good communication tactics at the start of each meeting (face those with hearing loss, light on face, speak clearly, take turns rather than talk over others)

- Actively encouraged steering group members to stop the conversation if at any point they were struggling to hear, so that communication could be reassessed.

- Reflected upon communication success as a group at the end of each meeting so as to be able to adapt our approach to our new learnings.

These ground rules were highly valued by all steering group members, not just those with hearing loss, as they were reassured that the process was fully inclusive.

These ground rules were mirrored in the final workshop, which was facilitated by three independent advisors and featured real-time speech-to-text communication support.

Figure 5: A patient at the final workshop makes use of his wireless microphone to aid communication

Figure 6: In the final workshop, while David Crowe (James Lind Alliance Advisor) spoke, real-time speech-to-text reporting was reproduced on a screen

Valuing and evaluating the impact of co-producing research

The JLA method offers a process that is inherently co-produced, both in conduct and in output. By providing patients, their family, friends and clinicians with a direct-line of communication to research funders, we begin the process of getting their most important questions answered.

“This process could not have been completed without true co-production. The key benefit is the respect and value put on every participant, be it in a steering group meeting, or the final workshop – every footprint counts.

All JLA PSP partnerships are co-productions by their very nature. Our project was not unique in so doing, but rather exemplifies how co-production research works in the JLA. We felt that by spotlighting ours, we have demonstrated how co-production can work from the very outset, by setting the research agenda for priority research to follow.” Jean

Figure 7: Participants at the final workshop literally voted with their feet, in order to rank and re-rank the unanswered questions for future research.

Figure 8: Discussion at the final workshop was intense; participants knew the final choices could one day influence their own hearing healthcare.

Flexibility

Although as a team, we came equipped with the JLA guidance and specific knowledge about pre-existing research into mild to moderate hearing loss, engaging with the PSP steering group and wider stakeholder groups required us to be continuously flexible. We had to learn how to communicate information to all stakeholders. We used novel techniques such as real-time speech-to-text reporting to ensure those with hearing loss were fully supported in their communication needs. We also created space for patients to seek clarification and to find ways to simplify our explanations by promoting an open two-way dialogue, overseen and facilitated by the JLA Advisor, David Crowe. Although we study hearing loss, we also had more to learn about how to help those with hearing loss hear, communicate and collaborate throughout the PSP process. We achieved this through iterative consultation and inclusion at every stage of the process, for each decision made.

Ongoing dialogue

“I suffer from something I call ‘Shrugged Shoulder Syndrome’. This means that when you ask your consultant, audiologist, GP, whomever: why did I lose my hearing suddenly? Might I have done something to make it happen? How can I prevent a recurrence? Am I more likely to get it again than someone who has never had it? What is the connection between the ringing in my ears and my lost hearing? The common answer is shrugged shoulders. We don’t know. Medical research hasn’t come up with answers to your question. We think it might be A but on the other hand it could just as easily be B.