Topic:

Resource type:

Authors:

Publication date:

Date added to Learning for Involvement:

Supporting equity and tackling inequality: how can NIHR promote inclusion in public partnerships?

An agenda for action

Candace Imison, Meerat Kaur, Shoba Dawson

Contents

Foreword

Much of my personal experience in forming a view about inclusion, particularly in health research and involving the public in the debate, has been based on my family, particularly as my first generation ‘Windrush’ parents became older and more dependent on healthcare services.

They were totally bemused with the language and terminology, thinking they were not educated or articulate enough to be engaged. I have a strong memory of my father looking helplessly at me when 2 health practitioners were talking over him about the design of a healthcare package. Yet, my parents were political animals, passionate about the development of their children and grandchildren, and they read everything there was to read about civic and social duties.

Why were they so afraid or uninterested in health research? I now realise it was because no-one asked them about their experiences or views in the culture and language of their heritage. I have since discovered this to be true of other minority groups who in the main are the most disadvantaged.

This Agenda for Action must be seen as a long-term process and not a quick fix in developing a relationship with diverse and dynamic communities that have enriched and contributed to our nation.

Angela Ruddock – Public Contributor – Project & Research Team

When we started on this review, I worried about what we could actually positively achieve as the agenda is huge and complex. However, the subject is much too important and growing in urgency to put back into the ‘too difficult to do’ box, as it often is. Further into the project, when engaging with a wider group of public contributors, they too sighed. We’ve all been here so many times before, yet without satisfactory resolution.

I was once helped in my thinking by another long-term service user. They said that we should learn to celebrate diversity, to be aware of our own prejudices, and shouldn’t see difference as a threat. We should indeed be positive about our difference. In trying to tackle health inequalities, we need to form public partnerships in research with the very people we ought to be helping the most. Co-produced research leads to better understanding and appropriate health and care response. The time is now…

Tina Coldham – Public Contributor – Project & Research Team

Executive Summary

“Culture change is at the heart of this. Otherwise we are involving underserved communities in an environment that isn’t fit for purpose. We need to explicitly acknowledge the things that are challenging, including research hierarchies, in order for anything to change.”

Lynn Laidlaw, Public Contributor, Steering Group Member

This report sets out an Agenda for Action within the NIHR and the research it funds and supports. The Agenda aims to promote health equity and reduce health inequalities through greater inclusion in public partnerships. This narrative Review is based on a range of evidence, including published studies, stakeholder feedback and grey literature. A steering group with relevant academic and lived experience expertise guided the Review and helped generate actionable insights.

The term public partnerships describes ways in which patients, service users, carers and members of the public work with researchers, and health and care professionals, in the creation and use of health and care research. This includes all activities in involvement, participation and engagement. Inclusive partnerships need to recognise the constellation of factors that give each of us our unique perspective, based on our experience of discrimination and privilege. These unique perspectives should be seen as assets, and opportunities to strengthen health and care research.

The NIHR aims for equality in involvement, engagement and participation in the research it funds and supports. Despite some excellent practice, the NIHR recognises that this ambition is yet to be achieved. This review heard widespread frustration at the lack of progress. There are systemic challenges facing the research and wider community in achieving that ambition. A long history of exclusion in society has left a legacy of deep-seated health inequalities. Exclusion from society has also led to the lack of inclusion in research and practice, which further increases health inequalities. This then reinforces the disadvantage embedded in wider society and culture. We need to break the cycle of exclusion and inequality.

To do this, the relationship between research institutions, researchers and communities needs to change. We should not expect the public to fit into research systems. Instead, we need to help researchers get closer to communities. We need to give communities the platform and power to influence and initiate research. We need to address the current mistrust of research and researchers, and replace it with trust. This is not only about race but all marginalised and underserved communities.

The NIHR has opportunities to strengthen inclusion and diversity across the research cycle. To change the culture and ways of working, four related issues need to be addressed.

- Resources – the time and money to overcome barriers to engagement and support inclusive partnerships.

- Partnership skills – to help research teams, university staff, health professionals and engagement leads engender trust and develop reciprocal relationships with communities, respecting and valuing different knowledge bases.

- Wider incentives – to create inclusive partnerships. For example, funders’ expectations of research teams and wider criteria for academic success and progression. These need to foster a diverse research workforce as well as inclusive research approaches

- Personal motivation – reinforced by all the above, to engage, share power and create a meaningful partnership.

The Review has identified notable examples of good practice within and outside of NIHR (see Appendix C). Many researchers are already working with communities, and building trusting relationships in collaborative partnerships that empower people. Drawing on evidence from the literature alongside stakeholder feedback and a systematic analysis of the NIHR’s current activities, we have identified opportunities for NIHR to strengthen inclusion and diversity across the research cycle.

NIHR can support more inclusive public partnerships through:

A. Increased funding

Ring-fence a proportion of research funding to support more inclusive engagement. Provide grants (pre and post award) for researchers to establish and sustain community relations, including in dissemination. Implement the learning from existing initiatives. This would help collaborative teams to deepen their expertise and relationships; and allow NIHR to learn how to effectively provide such funding.

B. More joined-up infrastructure

Inclusion cannot be achieved on a project by project basis. Individual research projects are at risk of reinventing the wheel; they cannot provide the foundation for long-term relationships. There is a need to develop and support regional hubs to coordinate activities across the NIHR and with other partners (e.g. NHS organisations and local authorities). Hubs could build relationships of trust with different communities, as the basis for their engagement with research. Hubs could build on the best of what different parts of NIHR already do, and join it up. They could strengthen relationships with community organisations and groups. They could support new roles for brokers/mediators and champions and have the resources to pay for engagement and support.

C. Support, guidance and training

- Establish a strengthened “good practice” repository on Learning for Involvement signalled via NIHR guidance.

- Establish a more formal mechanism to share best practice across research funders.

- Offer coordinated cross-NIHR training on how to promote inclusion in public partnerships. for researchers, NIHR programme staff, public contributors, and public partnerships staff.

D. Strengthening the role of public contributors, and the focus on public partnerships, in funding panels/committees

- Effective scrutiny of public partnership plans. Encourage committees to assess public partnership plans more robustly, e.g. by checking them with studies’ public contributors.

- Develop and support public contributors on committees.

- Encourage innovation. Committees need support to develop and improve. They need time to create a shared vision for public partnerships and to experiment with innovative forms of involvement and engagement.

E. Priority setting that reflects the needs of communities

All funding calls, including proposals for researcher-led calls, should demonstrate that they have taken account of the priorities and experiences of those facing inequalities. This could include linking funding calls to the NHS’s Core20Plus5 programme which identifies specific populations with the worst health access, experience, and/or outcomes.

F. Using NIHR’s influence to promote more inclusive public partnerships

Many EDI issues are systemic. NIHR therefore needs to work with applicants’ host organisations and sponsors and funders of research on the wider challenges. Stakeholder feedback during this Review gave a clear message that change is needed not only within the NIHR but in academia more widely. The NIHR could encourage this by:

- advocating for training on equality, diversity and inclusion for ethics committees

- advocating for reward for inclusive public partnerships in the REF

- establishing a formal mechanism for sharing best practice by research funders

- clarifying its expectations of applicants, sponsors and other funders in regard to EDI.

G. Prioritising inclusion in research on research

Inclusion should be a core priority within the research on research agenda. This means:

- periodic audit of funded research participation and involvement plans, to assess outcomes.

- assessment of the impact of public contributors on funding committees through ethnographic/qualitative research.

- research that informs good practice in partnerships between researchers and marginalised communities

- all research on research, including its priority-setting, should be supported by inclusive public partnerships.

H. Improved dissemination to trial participants and underserved communities

A deeper understanding of health literacy is needed, and of how to disseminate research findings to underserved communities. Those who have taken part in research should be systematically informed of trial outcomes. This could be mandated as part of trial funding.

I. Improved monitoring

To drive improvement, we need a better understanding of the level of diversity in public partnerships across the whole research cycle, from priority setting through to dissemination. There should be routine monitoring of diversity in public partnerships across all NIHR programmes. Building on the wider EDI strategy, guidance is needed on data definitions and governance.

J. Revisiting the supporting questions for the UK Standard for Public Involvement in Research

During our Review, stakeholders asked whether the wording of questions in the UK Public Involvement Standard for Inclusion should be revisited. They are currently framed as “offering opportunities” rather than as a genuine partnership. We would like the Five Nations Public Partnership Group to consider this feedback.

K. A more diverse research workforce

Creating a more diverse research workforce is a core priority in the forthcoming NIHR EDI strategy. The success of this agenda will be critical to supporting more inclusive public partnerships.

L. Alignment with relevant NIHR strategic activity

NIHR is supporting significant activity related to this agenda, including the Under-served Communities programme,the EDI programme and strategy, REPAG and the Race Equality Framework, plus the programme of improvement which is being overseen by the Public Partnerships Programme Board. Coordination across the NIHR to bring these strands of work together, will ensure that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

Over the next few months, these recommendations will be worked up into more specific actions that align with, and support, the wider EDI agenda within NIHR. This includes the EDI strategy, due to be published Autumn 2022. We will be seeking endorsement from NIHR leadership, so these recommendations can be taken forward in the work of the NIHR coordinating centres. This is an agenda, not just for the public partnerships community, but for the NIHR as a whole.

Introduction

This Review sets out an Agenda for Action within the NIHR and the research it funds and supports. The Agenda aims to promote health equity and reduce health inequalities through greater inclusion in public partnerships.

The term public partnerships describes ways in which patients, service users, carers and members of the public work with researchers, and health and care professionals, in the creation and use of health and care research. This includes all activities in involvement, participation and engagement.

Figure 1:

Full description of Figure 1:

Public Partnerships is made up of three areas: involvement, engagement and participation. These areas are all connected. Each of these terms is in a circle, and they are arranged in a triangle. Arrows go between each circle. Involvement encourages engagement, and engagement encourages involvement. Participation encourages engagement, and engagement encourages participation. Involvement encourages participation, and participation encourages involvement.

A steering group (membership listed in Annex B), with relevant academic and lived experience expertise, guided the Review. The steering group included 6 public contributors, one of whom was a member of the project team. Public contributors provided additional advice outside of the steering group meetings. A dedicated researcher with expertise in this area, Dr Shoba Dawson, worked collaboratively with a public contributor, Angela Ruddock, to support the Review. We also engaged, through events and interviews, with a range of stakeholders working in public partnerships at national, regional and local level.

The steering group was clear that the final output should be ambitious, and set out an Agenda for Action that would lead to change. The Review explores the wider barriers and enablers to inclusive research. But its recommendations are the actions that the NIHR needs to take.

This Review is not a systematic or comprehensive review of all relevant evidence and guidance. Rather, it is a narrative review based on a range of evidence, including published studies, stakeholder feedback and grey literature. Our steering group had relevant academic and lived experience expertise. This group guided the Review and helped generate actionable insights.

How this report is structured:

- Why promote inclusion in public partnerships?

- The underlying challenges

- The NIHR and the wider context

- How the NIHR is addressing the underlying challenges and the opportunities for improvement

- Recommendations for action and next steps

Why promote inclusion in public partnerships?

“Health and social care research also has a fundamental role to play in helping to reduce the disparities that exist in health outcomes caused by socio-economic factors, geography, age and ethnicity. Working with partners, NIHR needs to tackle the ingrained injustices that exist in the world of research in terms of who is involved, engaged or participating…”

Professor Chris Whitty, Dr Louise Wood,

Best Research for Best Health: The Next Chapter (2021) – NIHR’s current operational priorities.

“We get better science if we are more inclusive”

Professor Lucy Chappell #nihramc21

In the research it funds, the NIHR aims for equality in involvement, engagement and participation. However, respondents to the most recent NIHR Public Involvement Feedback Survey (2020-2021) were predominantly female (57%), 61 years of age and over, White and heterosexual. These public and patient contributors to the NIHR’s work and research highlighted barriers to effective engagement. A key recommendation was to “Support and engage more diverse people to be involved in the NIHR’s work and research to ensure we involve people with a range of knowledge, skills, and experiences”.

A recent study (Bower et al, 2020) found that geographical areas where a disease has most impact, have the lowest numbers of people taking part in related research. This means that diseases which are more common in deprived communities are being studied in healthier populations. The mismatch between the profile of research participants, and the populations who should benefit from the research,means that:

- benefits and side effects of treatments may not translate to real-world patients

- interventions may not be deliverable or applicable to all groups of patients

- findings specific to different populations may be overlooked

- some groups are discriminated against

- changes to health and social care services, based on research recommendations, may not be appropriate for, or acceptable to, everyone.

The recent rapid evidence review of ethnic inequalities in healthcare by the NHS Race and Health Observatory found similarities in experiences of health and care across people from ethnic minority backgrounds. There was a lack of high quality ethnic minority data for research purposes (Kapadia et al, 2022). This, and the lack of inclusion in many studies, means that artificial intelligence could worsen these inequalities (Leslie et al, 2021).

Different ethnic minority groups have different access to, experiences of, and outcomes from health and care services. These differences need to be understood for inequalities to be tackled. In 2015, the NIHR set out its ambition for public partnerships in Going the Extra Mile. This report stressed that unless inclusion in public partnerships is addressed, inequalities in health could get worse.

Public involvement must be diverse and inclusive to enable research that has the potential to reach those that stand to benefit from it most, and thus address issues of health equity

(Islam et al, 2021).

If public partnerships are not inclusive, or if people do not have a genuine opportunity to influence decisions, it undermines the benefits of partnership.

“Our findings suggest that we need more research that acknowledges, investigates and reports on the negative impacts of attempts at public involvement in health research and metrics that measure such involvement. We must ask questions about ways in which public involvement could increase inequalities, distort and suppress rather than amplify particular voices and agendas”

(Russell, Fudge and Greenhalgh, 2020)

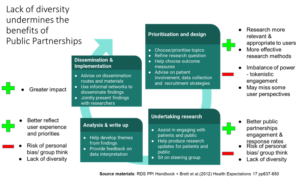

Figure 2 maps out the opportunities for public partnerships at all stages of the research (adapted from p14 RDS PPI Handbook). Against this we have identified some of the key benefits (+) and risks (-) from public partnerships (using Brett et al, 2012). If the public partnership is not inclusive it undermines the benefits and magnifies the risks.

Figure 2:

Full description of Figure 2:

The research cycle is made up of different stages including: prioritisation and design; undertaking research;, analysis and write up, and dissemination and implementation. Each of these terms is in a box connected by an arrow to indicate a circular process. For each stage, the opportunities for public partnerships have been indicated in the box. The benefits and risks have also been identified and are indicated next to the relevant box with a plus sign and a minus sign respectively.

For prioritisation and design, public partnerships can help to: choose/prioritise research topics, refine research questions; choose outcome measures and provide advice on patient involvement, data collection and recruitment strategies. The benefits from public partnerships at this stage include research that is more relevant and appropriate to users and more effective research methods. The risks from public partnerships are an imbalance of power and tokenistic engagement and missing some user perspectives.

For undertaking research, public partnerships can help to: engage with patients and public, produce research updates for patients and public, and feed into the steering group. The benefits from public partnerships are better engagement and response rates. The risks are personal bias, group think and lack of diversity.

For analysis and write up, public partnerships can help to: help develop themes from findings and provide feedback on data interpretation. The benefits from public partnerships are better reflections on user experience and priorities. The risks from public partnerships are risk of personal bias, group think and lack of diversity.

For dissemination and implementation, public partnerships can help to advise on dissemination routes and materials, use informal networks to disseminate findings and jointly present findings with researchers. The benefits from public partnerships are greater impact.

The take home message from the diagram is that lack of diversity undermines the benefits of public partnerships. The source materials are the RDS PPI handbook and Brett et al (2012) Health Expectations 17 pp637-650.

Underlying challenges to be addressed

The organisation, Shaping Our Lives, produced the report, Beyond the Usual Suspects, which gives practical guidance on developing more inclusive public partnerships (Beresford, 2013). It describes aspects of who we are, which may not be obvious to others, but which can drive exclusion. Stigma can magnify the problem.

Examples include:

- equality issues – gender, ethnicity, culture, belief, sexuality, age, disability and class

- where we live – homelessness, living in residential services, in prison or secure services, travellers and gypsies

- communication issues – people who are deaf, blind or visually impaired, deaf and blind, those who do not communicate verbally, and people for whom English is not their first language

- impairments – dementia, neurodiversity, people with complex and multiple impairments

- unwanted voices – activists, for example, might be experienced and confident in challenging the status quo.

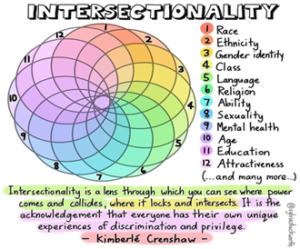

Inclusive partnerships need to recognise the constellation of factors that give each of us our unique perspective (see figure 3). This is ‘intersectionality’; we each have our own experience of discrimination and privilege. These unique perspectives should be seen as assets, and opportunities to strengthen health and care research.

Figure 3:

Full description of Figure 3:

Diagram heading reads intersectionality. “Intersectionality is a lens through which you can see where power comes and collides, where it locks and intersects. It is the acknowledgement that everyone has their own unique experiences of discrimination and privilege” – quote from Kimberlé Crenshaw. The diagram shows a rainbow of coloured circles, all slightly overlapping to form a larger circle. The circles are numbered from one to twelve and each circle represents a different characteristic. The characteristics listed are: race, ethnicity, gender identity, class, language, religion, ability, sexuality, mental health, age, education, attractiveness. There are many other characteristics that could be included.

Many scientific papers describe the challenges in developing inclusive public partnerships in research with excluded groups (see bibliography – Annex D). From this evidence, we pulled out two sets of challenges. The first are faced by patients, service users and members of the public. The second are faced by research teams and the organisations they work within. Successful partnerships will be aware of and will address these challenges.

Challenges faced by patients, service users, and members of the public

Public partnerships are more likely to succeed where researchers are aware that patients, service users and members of the public may:

- have had poor and traumatic experiences of research and statutory services

- have experienced stigma and been marginalised

- find it hard to trust you and to see why research would benefit us or those we care for.

- feel intimidated by you

- be embarrassed about our condition or personal circumstances

- find it difficult to express our views in front of people we don’t know

- not have access to digital tools or be able to use them easily

- not have English as our first language

- not be able to read or write easily

- not be able to hear or see easily

- find getting around difficult; we may not have a car or be able to use public transport

- have pressure on our time; we may be in full time work and unable to engage in normal working hours or we may have full time caring responsibilities

- not be clear about our role.

Challenges faced by research teams and the organisations they work in

Public partnerships are more likely to be inclusive and to succeed where researchers and their organisations:

- reinforce the value of public partnerships at all levels and recognise that culture and hierarchies need to change

- reflect the diversity of the communities they work with

- ensure inclusion is a priority for every individual in the wider team, including researchers, public involvement specialists and coordinators, methodologists, reception staff within research clinics

- have the skills and expertise to develop an inclusive partnership process and study design

- are sensitive to cultural context and reflect this in their communication, their engagement, and in the study design

- genuinely share power through authentic, equal and transparent partnerships in which everyone feels valued

- have the financial resources to support inclusive partnerships, and, for example, pay for people’s time, IT, transport or caring costs

- have sufficient time to develop meaningful public partnerships for individual studies and over the longer term

- carry out research on an issue of importance to a group or community, who can see how the research will make their lives better

- offer wider benefits to the community, by mentoring community members who, for example, could achieve an educational qualification as part of the research

- choose people who are known and trusted by the community to carry out the research.

As Ria Sunga of Egality said at a recent NIHR engagement event (Partnering with community organisations to increase diverse voices in research):

“There is no one way to address under-representation in research, it is a very complex issue, and one with many layers.”

To change the culture and ways of working, four related issues need to be addressed:

- Resources – the time and money to overcome barriers to engagement and support inclusive partnerships.

- Partnership skills – to help research teams, university staff, health professionals and engagement leads engender trust and develop reciprocal relationships with communities, respecting and valuing different knowledge bases.

- Wider incentives – to foster a diverse research workforce and inclusive approaches to research. Funders’ expectations of research teams, for example, and criteria for academic success and progression, need to reflect the importance of inclusive partnerships.

- Personal motivation – reinforced by all the above, to engage, share power and create a meaningful partnership.

“Very different ways of working in research are required – where you might start with a community. Research can be good at excluding people – to include them we really need new ways of thinking and working – real culture change. Signals from NIHR about culture and research ways of working have to be powerful and based on a clear set of values and embedded in methods.”

Professor Sophie Staniszewska, Warwick University, Personal Communication

NIHR & wider context

The NIHR report, Going the Extra Mile, Page 19, stated that:

“A diverse and inclusive public involvement community is essential if research is relevant to population needs and provides better health outcomes for all. We have been struck by the degree to which researchers and public contributors have encountered barriers when trying to work with different communities and populations”

Six years later, the engagement work undertaken to support the current NIHR improvement plan for public partnerships (NIHR: Next steps for partnership working with patients and the public, Kaleidoscope Health and Care) identified similar issues. That is, a recognition of the importance of inclusion but frustration at the lack of progress.

The lack of progress cannot be separated from the wider context in which health and care research occurs.

Initiatives such as the Athena SWAN charter demonstrate that interventions can improve gender equity and have a positive impact on equality, diversity and inclusion in academic settings. However, an evaluation of Athena SWAN found challenges to ongoing engagement with Athena Swan include a lack of resources, a lack of support from leadership, and the workload needed to ‘deliver a compelling application’ p55.

Marmot et al (2020) found that austerity had an increasing impact on the quality of life for individuals and communities in England from 2010 to 2020:

“From rising child poverty and the closure of children’s centres, to declines in education funding, an increase in precarious work and zero hours contracts, to a housing affordability crisis and a rise in homelessness, to people with insufficient money to lead a healthy life and resorting to food banks in large numbers, to ignored communities with poor conditions and little reason for hope. And these outcomes, on the whole, are even worse for minority ethnic population groups and Disabled people.”

Marmot et al, 2020

This analysis was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, which further exacerbated inequalities. The pandemic impacted the lives of ethnic minority communities, Disabled people or people with impairments, and those living with economic challenge. It also hit the organisations and charities that work with these groups. In this context, inclusion becomes even more important and yet the challenges are increasing.

The NIHR worked with the Health Research Authority, members of the public, patients, service users, other funders, regulators and research organisations to co-produce a Shared commitment to public involvement in research. This commitment builds on the learning from initiatives to strengthen public involvement in research during the COVID-19 pandemic. It ensures people’s perspectives and lived experiences shape the research being planned and delivered.

The shared commitment reiterates the NIHR’s previous assertion to improve inclusion in all that it does. Inclusion was featured as one of the organisation’s 5 operating principles in Best Research for Best Health: The Next Chapter (2021), along with impact, excellence, collaboration and effectiveness. The principle reads:

Inclusion. We are committed to equality, diversity and inclusion in everything we do. Diverse people and communities shape our research, and we strive to make opportunities to participate in research an integral part of everyone’s experience of health and social care services. We develop researchers from multiple disciplines, specialisms, geographies and backgrounds, and work to address barriers to career progression arising from characteristics such as sex, race or disability.

Elsewhere in the document is the pledge:

Expect all research funded and supported by NIHR to demonstrate meaningful, diverse and inclusive involvement, and to show the difference it makes, in line with the UK Standards for Public Involvement and using tools such as the Race Equality Framework.

The NIHR’s approach to public involvement is guided by the UK Standards for Public Involvement in Research (2019). Standard 1 on Inclusive opportunities states:

Offer public involvement opportunities that are accessible and that reach people and groups according to research needs. Research to be informed by a diversity of public experience and insight, so that it leads to treatments and services which reflect these needs.

Standard 1 states that for projects to be inclusive, they need to consider:

- Are people affected by and interested in the research involved from the earliest stages?

- Have barriers been identified and addressed through, for example, payment for time or accessible locations for meetings?

- How is information about opportunities shared, and does it appeal to different communities?

- Are there fair and transparent processes for involving the public in research, and do they reflect equality and diversity duties?

- Is there choice and flexibility in the opportunities offered to the public?

Under this standard, our steering group added:

- Can people genuinely impact the research process and design?

- Can opportunities be co-produced with, or led by, people and communities?

Equality, diversity and inclusion, was another major theme of Public Involvement in Social Care Research, a collaboration between the NIHR and SCIE (Social Care Institute for Excellence). Together, they explored how the NIHR could promote better public partnerships in social care research, and said:

“diversity has to be purposefully addressed – it cannot be left to chance”.

Many initiatives within the NIHR promote this agenda (see Annex C), but they currently lack a clear strategic framework and coordination.

“Clearly the commitment from health/social care leaders to increasing diverse and meaningful involvement is genuine, but we need the voices from those with stories and experiences to share with those leaders” Angela Ruddock, public contributor

The NIHR is committed to improving inclusion in all that it does. Most recently, the role of Head of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion was established and the first EDI strategy for NIHR is due to be published in Autumn 2022. It has 5 strategic themes.

EDI Strategy

The 5 themes are to:

- become a more inclusive funder of research

- widen access and participation for greater diversity and inclusion

- improve and invest in the NIHR talent pipeline

- embed evidence-led diversity and inclusion approaches

- collaborate with partners for impact and sustainability.

The output from this Review will inform the wider EDI strategy and we hope that, together, the Review and the wider strategy will provide a strong platform to argue for the support necessary for successful inclusive public partnerships. That means time, resources and funding.

NIHR: Opportunities for improvement

In this section, we explore evidence from the literature alongside the NIHR’s current activities, to illustrate opportunities for improvement. We conclude this section with a gap analysis of the whole funding cycle to identify areas of particular opportunity.

It is striking that it is relatively rare for publications to describe their own approach to public partnerships, including to diversity. The evidence we call on illuminates key issues, but also has its own limitations and does not reliably capture what matters to communities.

Additional time and resources

One of the most consistent messages from the literature is the need for additional time and resources to foster inclusive public partnerships in research. Building relationships of trust with communities is a time-, resource-, and labour-intensive process (Tembo et al, 2021).

“In any relationship, trust is essential. When you’re building a relationship, if there’s no trust there, you won’t have a very good relationship. So the Community is no different than anybody else. You can’t expect trust back from them, especially if they get the feeling that you don’t have their back or their interest at heart.”

Davine Ford, Public Contributor (NIHR event- Partnering with community organisations to increase diverse voices in research)

Demonstrating trustworthiness can be complex. Trust can be gained or challenged by multiple factors. Partners need to be engaged early and consistently (Heckert et al, 2020); funding calls and project timelines need to allow sufficient time to build relationships and engagement (Bryan et al, 2018, Bonevski et al, 2014). There is an inherent tension between the time needed, and the pressure to generate timely results that can inform clinical practice (Heckert et al, 2020). Stakeholders told us that the speed and timing of NIHR processes can prevent meaningful engagement and the building of trust. Methods that are culturally-appropriate, and can improve access, require funding. They might require interpreters, community brokers, IT equipment, training and mentorship, materials in varied formats and languages. In addition, more complex and less obvious needs can remain unseen, making involvement impossible. The true costs of participation are frequently underestimated (Batty, Humphrey, and Meakin 2022).

“One of the key things to support public contributors, or people with different experiences is providing the training. Giving them that support and building confidence can help them get their voices heard. They’ve got their lived experience, but they just need that support in terms of how you as institutions work and your processes.”

Kirit Mistry, South Asian Health Network (NIHR event- Partnering with community organisations to increase diverse voices in research)

Participant expenses are covered, but few NIHR funding calls make specific allowance for inclusive approaches. Our steering group pointed out that we fund university oncosts. Should we not therefore pay for community oncosts in the same way?

“And it is the responsibility of the researchers, because actually, by looking for the funding what you’re saying to them is – I value your lived experience as much as I value my knowledge. That’s where the equity comes.”

Davine Ford, Public Contributor (NIHR event- Partnering with community organisations to increase diverse voices in research)

Long term relationships with communities

Another consistent theme in the literature, reinforced by our steering group and those we engaged with, is the need for investment that isn’t tied into single research projects, but into long-term relationships (Hickey et al, 2022). Staniszewska et al (2022) talked about “glue money” to sustain relationships between researchers and communities outside of formal research projects.

A recent scoping review, conducted for the NIHR, stated:

“The fragmentation of regional NIHR public involvement resource into separate centres, programmes and projects, with finite contracts and funding, also impacts on the ability of public involvement teams to successfully build and maintain trusting relationships with public contributors and communities, and to build capacity. These relationships are crucial in supporting teams to develop and deliver e.g. funding bids within the short timescales demanded by NIHR funding panels. However, they require a significant amount of time and stable resource to establish and maintain. In the current model, individual research teams do not have the resource or capacity to reach out into local communities in anything other than a piecemeal way.”

Increasing Diversity on National Funding Committees: A Scoping Review – Smith, 2021

Islam et al’s (2021) proposed that:,

“Maybe there should be ‘how to involve researchers in communities’ rather than involving communities in research”

Islam et al (2021).

Our steering group strongly support this proposal.

Suggestions to sustain relationships with local communities include:

- Establish and use multiple links to diverse communities. For example, using engagement events, speaking opportunities and personal links with key individuals and organisations (Waheed et al, 2015, den Oudendammer et al, 2019)

- Build a list of brokers and mediators with strong links to diverse communities and fund them to engage and facilitate dialogue between funders, universities and these communities. (Bryan et al, 2018, Waheed et al, 2015, Bodicoat et al, 2021)

- Create a research participant registry for improved access to participants from disadvantaged communities (Bonevski at al, 2014).

- Provide spaces for engagement activities that are safe and welcoming (Bryan et al, 2018).

At several of our engagement events, people argued that a regional hub with permanent staff could help establish and maintain long-term relationships. A hub could pool funding, expertise and resources across different projects. It could support community networks in a region and avoid duplication.

Inclusion within research proposals

Funding panels and committees

Funding panels need to reflect the diversity of the UK population (Bryan et al, 2018, den Oudendammer et al, 2019). The NIHR should publish data on the ethnic make-up of decision-making bodies and on application-award success (Bryan et al, 2018). A recent scoping review for the NIHR (Smith, 2021) highlighted the lack of diversity on panels and variation in how they operate. Smith stated that panels of academics and clinicians can be a hostile environment for inexperienced public contributors, who can feel their contribution is tokenistic. Having a public contributor co-Chair was proposed as a way of raising the profile of the public voice within panels. The co-Chair might need support and training. Another proposed solution was restructuring the review process such that the public contributor speaks first instead of third.

“That system, I think, by its very nature, makes inclusion much more difficult because it makes people feel less welcome… it requires particularly sensitive chairing skills to help people be involved”

Graham, Public Contributor (NIHR event- Partnering with community organisations to increase diverse voices in research)

Staniszewska et al (2021) looked at public partnerships on funding committees/panels and made 16 high level recommendations, including:

- extending the diversity of committee membership

- greater feedback on public contributor experience

- developing a whole committee vision of public partnerships

- strengthening the voice of the public contributor in the committee’s operation.

Expectations of proposals

Engagement can start even before funding has been secured. In this way, partners can influence research questions and design, and encourage team building (Snape et al, 2014). Small grants from the NIHR Research Design Service have been helpful in promoting engagement in the development of applications (Boote et al, 2015). The NIHR should challenge proposals that fail to demonstrate a clear understanding of ethical partnerships (Bryan et al, 2018) or whose study design is not appropriate for the cultural context (George, Duran, and Norris 2014). Reviewers require training to assess inclusiveness and prioritise trials that sample underrepresented groups (Smart, 2021). Funders should provide examples of what a “good” proposal would look like (Bryan et al, 2018)

Upskill the research workforce

Working collaboratively with communities with diverse cultures and experiences requires training.

“Do we know how to engage? I know it sounds like a silly question. But in order to bring people along with us; do we know where to find them; do we include them in our planning stages; do you know what methods to use to involve them; do we know how people want to be involved? These are a few of the questions that come up time and time again.”

Davine Ford, Public Contributor (NIHR Event – Partnering with community organisations to increase diverse voices in research)

The community engagement conducted to support NIHR’s race equality framework demonstrated the importance of acknowledging that many communities have a history of “harm, betrayal, trauma” caused by racial injustices. As other research has highlighted (Ocloo et al, 21), there is wide mistrust of research and researchers. Addressing issues of mistrust, and the underlying imbalance of power, is critical to successful engagement (Banas et al, 2019, Bryan et al, 2018, Beresford, 2013). Waheed et al (2015) and others have encouraged cultural competency training for researchers and placements to help them appreciate community needs. However, some have challenged the concept of cultural competence, particularly in medical settings, as potentially simplifying cultures and overlooking the differences between people (Kleinman and Benson, 2006).

“Cultural humility” therefore becomes as important. This means individuals embedding a practice of “self-reflection and self-critique as lifelong learners…”

checking power imbalances that exist because of people’s roles, and

“develop[ing] and maintain[ing] mutually respectful and dynamic partnerships with communities…”

(Tervalon and Murray-García, 1998). Researchers will need to consider how they will build effective partnerships with community-based organisations (Turin et al, 2022) including through training and support.

“It takes time for researchers who are new to the field of co‐research or dementia to see people with dementia as individuals with knowledge and experience rather than members of a category associated only with impairment.”

(Waite, Poland, and Charlesworth 2019)

Researchers need to see the value of partnerships, to both researcher and participant, and to address the imbalance of power inherent in the relationship (Chambers et al, 2019). Participatory design principles and engagement techniques such as drama, video, pictures and objects can help redress the power imbalance (Broomfield et al, 2021, Bryan et al, 2018). Other techniques to strengthen reciprocal relationships and communication exist (Farr et al, 2021).

Inclusive partnerships support the dissemination of research outcomes

The evidence suggests that the dissemination of research frequently lacks inclusive public partnerships, even though partnerships can promote its reach and impact (Dawson et al, 2018).

“Is disseminating results to participants in language and terms they understand prioritised? There is a long way to go, currently only 10% of research gives the results to participants (HRA figures). If we aren’t doing this with existing research participants, how can we possibly hope to achieve it with underserved communities?”

Lynn Laidlaw, Public Contributor, Steering Group Member

Communities want to see the benefit and outcome of their engagement. Effective dissemination of outcomes is one way of doing this. Feedback needs to be relevant, accessible, and free from jargon (Farooqi et al, 2022). Recent research, commissioned by the NIHR from Kingston/St George’s University (Bearne et al, 2022), made a series of recommendations about how to reach more diverse communities. These include:

- more tailored approaches which use language and media (written or digital approaches, for example) familiar to each audience

- using trusted intermediaries to support communication

- including stories of lived experience.

Evaluate the impact of new approaches

Stakeholders we engaged with emphasised the need for experimentation and innovation, but said that new approaches to embed inclusive partnerships need to be evaluated. They felt the NIHR tends not to evaluate its own initiatives.

Resources are needed to evaluate public involvement (Boivin et al, 2018; Snape et al, 2014). Approaches for evaluation should be developed with people with lived experience (Laidlaw, 2021, Boivin et al, 2018), and should acknowledge the complexity, and capture the learning that is integral to this way of working (Boivin et al, 2018; Staley, Abbey-Vital, and Nolan 2017). Overall, there is a need for a more robust evidence base –

“Further progress towards making patient and other stakeholder engagement in research more widely practised can be made if researchers, stakeholders, institutions, funders, and policy makers learn together about the key challenges and act together through further research, capacity building, and policy change.”

(Heckert et al, 2020)

Whole system incentives and support for wider cultural change

Because many EDI issues are systemic, the NIHR needs to work with academia and other funders on the wider challenges. A strong message from our engagement with stakeholders during the Review was that change is needed not only within NIHR but in academia more widely. The NIHR needs to use its influence to encourage this.

“Culture change is at the heart of this. Otherwise we are involving underserved communities in an environment that isn’t fit for purpose. We need to explicitly acknowledge the things that are challenging, including research hierarchies, in order for anything to change.”

Lynn Laidlaw, Public Contributor, Steering Group Member

Incentives to promote inclusion are needed at individual, organisation and system levels (Ayton et al, 2021, Ocloo et al, 2021). They should be embedded and reported across the whole research system including institutions, ethics committees, journals and funders (Snape et al, 2014). Ethnicity data needs to be collected and used diligently (HSRUK et al, 2022).

This requires a culture change across the whole system. Inclusive public partnerships need to move from being a tick-box exercise to a valued agenda that is seen as core to delivering high quality research and impact.

“If this doesn’t happen, then we will get a tick box EDI, eg researchers saying to PPI leads “find me a public contributor with certain characteristics such as ethnic community etc”

Lynn Laidlaw, public contributor, Steering Group Member

Without culture change we risk involving underserved communities in an environment that could cause as much damage as benefit to those who we engage with.

The Runnymede Trust set out 10 principles for community-university partnerships to promote non-exploitative relationships.

The 10 commitments are to:

- strengthen the partnering community organisation

- seek mutual benefit

- transparency and accountability

- fair practices in payments

- fair payments for participants

- fair knowledge exchange

- sustainability and legacy

- equality and diversity

- sectoral as well as organisational development

- reciprocal learning

Standardised methods for recording diversity

Recent work by Egality, working with medical research charities, highlighted that ethnicity data is not routinely collected. This means organisations and the research sector don’t know the diversity of participants currently involved in research, and don’t have a benchmark to measure improvement. The lack of standardised methods and inclusive categories means researchers don’t feel equipped to record ethnicity. Egality recommended that national bodies work together to develop standardised methods and inclusive categories to help researchers to record and report ethnicity.

Reinforcement within academia

The published literature singles out the frequent mismatch between support for co-production, which takes time, and academic incentives, including the Research Excellence Framework (REF), which rewards researchers for the number of publications they produce. Feedback from stakeholders, including our steering group, highlighted the challenges created by short-term contracts for researchers, and the wider pressures that academics are under. Public engagement often struggles to compete for time and resources within the context of a system driven by reward and recognition for research itself (Hamlyn et al, 2015).

“Even good intentions and well-planned engagement activities can be diverted

within the existing research funding and research production systems where non-research stakeholders remain at the margins and can even be seen as a threat to academic identity and autonomy.”

(Boaz et al, 2021)

Academia and research funders need to value interdisciplinary and team science, and the skills that foster co-production (Tembo et al, 2021). As a key stakeholder in REF development, and a significant funder of University activity, the NIHR could promote the value of inclusion.

The Research Excellence Framework could incorporate a mechanism that values and rewards the outputs of co-production (for example the total number of peer-reviewed articles that are single authorship or lead authored with community partners; evaluating how the research contributed to strengthening local community participation, skills building, research literacy, or creative engagement) and measures the effect of research on people’s lives.”

(Tembo et al, 2021)

Diversity within the research workforce

A more diverse research workforce will encourage and support more inclusive public partnerships (Chambers et al, 2017, Prinjha et al, 2020). Action is needed to encourage this.

“This is not said enough times. The makeup of the workforce is so important in improving and ensuring real dialogue and collaboration.”

Angela Ruddock, Public Contributor

Marginalised academics lack visibility, even within research on diversity, equity and inclusion, and are often employed on zero hours contracts (HSRUK et al, 2022). The commitment to end discrimination on the grounds of race, ethnicity, religion, language or cultural tradition needs to be made explicitly. It needs to be part of the grant awarding processes, including peer review. (Bryan et al, 2018)

Action across the whole research cycle

Partners should have the opportunity to be involved at every stage: from setting priorities and questions to data collection, analysis and dissemination (HSRUK et al, 2022). Engagement across the whole research cycle from the initial concept to implementing findings can help engender trust in research (George et al, 2014).

Below we assess the degree to which NIHR promotes inclusion across the research cycle. This highlights the opportunities for improvement at all stages. This assessment informs the final recommendations.

“The widening of involvement needs to occur in all research stages from prioritisation of topics, through conceptualising projects, commissioning processes, conducting studies and reporting and seeking impact from them”

(Clark et al, 2021 p1547)

Assessment of current NIHR support for inclusive engagement

Engagement is essential across the research cycle. Here we look at:

- Deciding on research priorities

- Making funding decisions

- Supporting research design and delivery

- Supporting the dissemination of research findings

- Evaluating the outcomes of research

- Working with other funders to share best practice

- Whole system action – including a more diverse research workforce

Deciding on research priorities

Current support

- James Lind Alliance (JLA) brings patient, carer and clinician groups together on an equal footing to identify research priorities using inclusive communications methods. JLA is a pilot partner for the NIHR’s race equality framework. Its work informs the priorities of the Health Technology Assessment and other NIHR research programmes. Research on the JLA has shown that the priorities of people living with conditions differ distinctly from those delivering care (who often conduct the research); there is also a need to strengthen the influence of those with lived experience on funding and funders (Staley et al, 2020).

- Research for Patient Benefit

Working with Public Contributors to develop a Proposal Development Grant call for proposals that work with PPI in novel and innovative ways within communities and as partnerships. The call will be launched in Summer 2022

The NIHR Public Health Research Programme has launched funding calls which encourage inclusion of geographic populations which have been historically under-served. The calls aim to boost research in the areas with the greatest health needs. Past examples include:

- Increasing uptake of vaccinations in populations where there is low uptake

- Digital health inclusion and inequalities

- What are the health and health inequality impacts of being outdoors for children and young people?

Potential for improvement

- Routine monitoring of inclusion (public partnerships) in priority setting across all NIHR programmes.

- All funding calls, including proposals for researcher-led calls, should demonstrate that they have taken account of the priorities and experiences of those facing inequalities.

- Funding should be available to support community engagement in developing proposals.

Making funding decisions

Current support

- PPI guidance for NIHR applications encourages diversity but there is no data to tell us how systematically it is adhered to.

- NIHR Funding Committees/Panels currently lack diversity, including among their public contributors.

- HSDR is trialling an approach in which equality, diversity and inclusion is assessed when applications are reviewed; ‘inclusion observers’ provide feedback.

- NIHR’s Global Health Research programme expects all research to be undertaken in collaboration with the communities most likely to be affected by the research outcomes. It provides guidance on participatory approaches.

Potential for improvement

- Routine monitoring of inclusion (public partnerships) on panels.

- More robust assessment of public partnership plans potentially checking them with public contributors.

- Regular audit to check outcomes of participation and involvement plans for funded research.

- More systematic feedback on the experience of public contributors on funding panels/committees.

- Explore the impact of public contributors on funding sub-committees through ethnographic and qualitative research.

- Provide support for the development and improvement of committees. They need time to create a shared vision for public partnerships and to experiment with innovative forms of engagement.

Supporting research design and delivery

Current support

- NIHR has provided researchers with support. For examples and prompts for best practice, see Annex C.

- NIHR Digital strategy is developing a research registry to support more diverse engagement.

- The NIHR Patient Engagement in Clinical Development Service is encouraging life science companies to involve patients to “help shape and improve the design and, ultimately, the delivery of commercial clinical research”.

- Services connect specific population groups with research. This includes ensuring children and young people influence new medical devices and medical technologies.

- Many examples of NIHR fora and approaches are connecting people and communities from diverse backgrounds (including young people, homeless populations etc) with researchers.

Examples of additional support for engagement: regular, small amounts of funding from the NIHR Research Design Service for engagement in the development of grant applications; a NIHR pilot funding programme provided up to £10,000 for proposals to strengthen public partnerships in specific regions/geographies; larger funds to ‘Develop innovative, inclusive and diverse public partnerships’.

- Payment for PPI engagement; guidance on how to pay.

Potential for improvement

- Provide separate funding to support more inclusive and community engagement.

- Routine monitoring of the degree to which public partnerships in research were genuinely inclusive

- Lack of long-term relationships but regional infrastructure for PPI is being explored and mapping work undertaken. A proposal for regional hubs is being developed by NIHR for consideration by DHSC.

- Encourage follow on applications that allow collaborative teams to deepen their expertise and relationships.

- NIHR guidance to strengthen a repository of examples of good practice.

Supporting the dissemination of research findings

Current support

- Open Access Policy

- NIHR Evidence – providing accessible summaries of NIHR outputs with public contributors on the editorial board, and as reviewers.

- Learning from research on how to better reach underserved communities.

- Guidance to create inclusive content and language

- Journals Library – Reporting Equality, Diversity and Inclusion in PPI (nihr.ac.uk)

- The National Elf Service disseminates good quality evidence from multiple sources in accessible ways, and the NIHR School of Social Care is one of the organisations behind the Social Care Elf.

- The NIHR-funded Piper Study starting in Autumn 2022 is exploring the role of patients and the public in the implementation of evidence into practice.

- Co-creating communication, engagement and dissemination with minoritised communities and ensuring outputs are accessible.

Potential for improvement

- Require researchers to feedback to communities and research participants on the outcome of the research they have participated in.

- Engage communities around what dissemination approach works best for them and who they feel should be the target audience e.g. are these messages GPs need to hear?

- Act on audience research findings, including insights about health literacy, to better reach underserved communities.

Evaluating the outcomes of research

Current support

- No systematic use of inclusive public partnerships in NIHR’s research on research and evaluation programme.

Potential for improvement

- Inclusion should be a core priority within the research on research agenda.

- Systematic public engagement in setting priorities for and engagement in research on research and evaluation.

Working with other funders to share best practice

Current support

- NIHR works closely with HRA and others – see shared commitment to “meaningful, diverse and inclusive involvement”.

- NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme has been working with PCORI, sharing best practice in engaging patients, stakeholders, and underserved groups in research.

Potential for improvement

- Establish a more formal mechanism to share best practice in this area across research funders.

- Create consistent monitoring variables.

Whole system action – including a more diverse research workforce

Current support

- NIHR feeds into REF reviews.

- NIHR Academy encouragement of diversity in NIHR research professorships

- NIHR forthcoming EDI strategy will address diversity across NIHR

- Vocal in Greater Manchester is an example of shared infrastructure for inclusive public partnerships, resourced by health and care research initiatives across a region and shaped with people and communities from diverse backgrounds or with varied experiences to articulate and respond to local priorities.

Potential for improvement

- Advocate training for ethics committees on equality, diversity and inclusion and partnership working

- Advocate for equality, diversity and inclusion and reward for inclusive public partnerships in the REF.

- Ensure forthcoming NIHR EDI strategy includes action to monitor and address diversity in the research workforce.

Conclusion, recommendations for action & next steps

A long history of exclusion in society has left a legacy of deep-seated health inequalities. Exclusion from society has led to the lack of inclusion in research and practice, which further increases health inequalities. These inequalities then reinforce the disadvantage embedded in wider society and culture. We need to break the cycle of exclusion and inequality.

In order to do this, our steering group and those we engaged with, told us that we need to reframe the relationship between researchers and communities. We need to ensure that people have the platform and power to influence, inform and initiate research.

We should not expect the public to fit into research systems. Instead, we need to help researchers get closer to communities. NIHR needs to create systems to facilitate this. In particular, systems that can help redress the imbalance of power and the mistrust frequently felt by communities towards research and researchers. For communities, research is not an end in itself but should be a route to a better life. This connection is rarely seen. Inclusion is not only about race but all marginalised and excluded communities. The whole system needs a change of culture. Inclusive public partnerships need to move from being a “tick box exercise” to a valued agenda that is core to delivering high quality research and impact. This will take time, resources and effort, along with a significant change in research culture.

While this Review explores the wider barriers and enablers to inclusive research, its recommendations are directed towards the actions that NIHR needs to take. The Review has identified notable examples of good practice within and outside of NIHR (see Appendix C). Many researchers are already working with communities, and building trusting relationships in collaborative partnerships that empower people. We have identified many opportunities for NIHR to strengthen inclusion and diversity across the research cycle.

NIHR can support more inclusive public partnerships through:

A. Increased funding

Ring-fence a proportion of research funding to support more inclusive engagement. Provide grants (pre and post award) for researchers to establish and sustain community relations, including in dissemination. Implement the learning from existing initiatives. This would help collaborative teams to deepen their expertise and relationships; and allow NIHR to learn how to effectively provide such funding.

B. More joined-up infrastructure

Inclusion cannot be achieved on a project by project basis. Individual research projects are at risk of reinventing the wheel; they cannot provide the foundation for long-term relationships. There is a need to develop and support regional hubs to coordinate activities across the NIHR and with other partners (e.g. NHS organisations and local authorities). Hubs could build relationships of trust with different communities, as the basis for their engagement with research. Hubs could build on the best of what different parts of NIHR already do, and join it up. They could strengthen relationships with community organisations and groups. They could support new roles for brokers/mediators and champions and have the resources to pay for engagement and support.

C. Support, guidance and training

- Establish a strengthened “good practice” repository on Learning for Involvement signalled via NIHR guidance.

- Establish a more formal mechanism to share best practice across research funders.

- Offer coordinated cross-NIHR training on how to promote inclusion in public partnerships. for researchers, NIHR programme staff, public contributors, and public partnerships staff.

D. Strengthening the role of public contributors, and the focus on public partnerships in funding panels/committees

- Effective scrutiny of public partnership plans: encourage committees to do more robust assessment of public partnership plans, eg by checking them with studies’ public contributors.

- Develop and support public contributors on

- Encourage innovation. Committees need support in order to develop and improve. They need time to create a shared vision for public partnerships and to experiment with innovative forms of involvement and engagement.

E. Priority setting that reflects the needs of communities

All funding calls, including proposals for researcher-led calls, should demonstrate that they have taken account of the priorities and experiences of those facing inequalities. This could include linking funding calls to the NHS’s Core20Plus5 programme which identifies specific populations with the worst health access, experience, and/or outcomes.

F. Using NIHR’s influence to promote more inclusive public partnerships

Many EDI issues are systemic. NIHR therefore needs to work with applicants’ host organisations and sponsors and funders of research on the wider challenges. Our engagement during this Review gave a clear message that change is needed not only within the NIHR but in academia more widely. The NIHR could encourage this by:

- Advocating for training on equality, diversity and inclusion for ethics committees.

- Advocating for reward for inclusive public partnerships in the REF.

- Establishing a formal mechanism for sharing best practice by research funders.

- Etrengthening what NIHR says regarding its clear expectations of applicants, sponsors and other funders in regard to EDI.

G. Prioritising inclusion in research on research

Inclusion should be a core priority within the research on research agenda. This means:

- Periodic audit of funded research participation and involvement plans, to assess outcomes.

- Assessing the impact of public contributors on funding committees through ethnographic/qualitative research.

- Research that informs good practice in partnerships between researchers and marginalised communities.

- All research on research, including setting research on research priorities, should be supported by inclusive public partnerships.

H. Improved dissemination to trial participants and underserved communities

A deeper understanding of health literacy is needed and how to disseminate research findings to underserved communities. Those who have taken part in research should be systematically informed of trial outcomes. This could be mandated as part of trial funding.

I. Improved monitoring

To drive improvement, we need a better understanding of the level of diversity in public partnerships across the whole research cycle from priority setting through to dissemination. There should be routine monitoring of diversity in public partnerships across all NIHR programmes. Building on work in the wider EDI strategy – guidance is needed on data definitions and governance.

J. Revisiting the supporting questions for the UK Standard for Public Involvement in Research

During our Review, stakeholders asked whether the wording for the current questions for the UK Public Involvement Standard for Inclusion should be revisited. They are currently framed as “offering opportunities” rather than as a genuine partnership. We would like the Five Nations Public Partnership Group to consider this feedback.

K. A more diverse research workforce

Creating a more diverse research workforce is a core priority in the forthcoming NIHR EDI strategy. The success of this agenda will be critical to supporting more inclusive public partnerships.

L. Alignment with relevant NIHR strategic activity

NIHR is supporting significant activity related to this agenda, including the Under-served Communities programme,the EDI programme and strategy, REPAG and the Race Equality Framework, plus the programme of improvement which is being overseen by the Public Partnerships Programme Board. Coordination across NIHR to bring these strands of work together will ensure that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts.

Next steps

Over the next few months, these recommendations will be worked up into more specific actions that align with and support the wider EDI agenda within NIHR, including the EDI strategy to be published in Autumn 2022. We will be seeking endorsement from NIHR leadership, so they can be taken forward in the work of the NIHR coordinating centres. This is an Agenda, not just for the public partnerships community, but for the NIHR as a whole.

Paper authors and how to cite this report

Candace Imison, Meerat Kaur, Shoba Dawson

Imison C, Kaur M, Dawson S. Supporting equity and tackling inequality: how can NIHR promote inclusion in public partnerships?, An agenda for action; August 2022, [URL], (Accessed on: [DATE])

Annex A – Glossaries

Glossary – Equality, Diversity and Inclusion

Access and Outreach – the activity undertaken to support underrepresented groups to access higher education. This may include:

- Sustained and progressive programmes of targeted outreach with schools, colleges and job centres.

- Broader collaborative activities with employers, third sector organisations and other education providers.

Advocate – someone who speaks up for themselves and others, e.g. a person who lobbies for equal pay for a specific group.

Carer and Caring responsibility – a carer is a person who has total or substantial responsibility for helping and supporting another person. This could be a partner, a parent, a child, other relative, friend or neighbour. This might be necessary because of age, physical or mental illness, learning difference, addiction, disability, or other factors. A carer can be an adult, child or young person.

Cognitive diversity – the different perspectives, ways of thinking and different skill sets that people from different backgrounds and diverse experiences have. In an EDI context, it is often used to emphasise the benefits of including different people in order to provide a variety of perspectives, ways of thinking and ideas.

Dignity – a value owed to all humans, to be treated with respect.

Diversity – everyone is different in a variety of visible and non-visible ways, and that those differences are to be recognised, respected and valued.

Equal opportunities – or equality of opportunity, ensures that everyone is entitled to freedom from discrimination, and has an equal opportunity to access opportunities and fulfil their potential. The term ‘equal opportunities’ has mostly been replaced by ‘equality, diversity and inclusion’ in recent years.

Equality – is about ensuring that every individual has an equal opportunity to make the most of their lives and talents. Noone should have poorer life chances because of where, what or whom they were born, or because of other characteristics. Equality recognises that certain groups of people with particular characteristics e.g. those of a certain race, with disabilities, women, gay and lesbian people etc, continue to experience discrimination.

Equality Impact Assessment – is abbreviated to EIA or sometimes EQIA. A detailed and systematic analysis determines how a policy, procedure or change to process may disproportionately impact a particular group.

Equity – the proposition that individuals should be provided with the resources they need to have access to the same opportunities as the general population. Equality indicates uniformity and the even distribution of resources among all people. However, equity represents the distribution of resources in such a way as to meet the specific needs of individuals. It acknowledges that some groups and individuals require more or less resources in order to access the same opportunities as others. Treating everyone equally does not necessarily lead to equality; equal treatment often perpetuates existing hierarchies.

Human rights – the basic rights and freedoms to which all humans are entitled. They ensure people can live freely and are able to flourish, reach their potential and participate in society. These rights help to ensure that people are treated fairly and with dignity and respect. An individual has human rights by virtue of being human and they cannot be taken away.

Identity – the characteristics and qualities of a person, considered collectively, which are essential to that person’s self-awareness. A dimension of an individual’s identity is their relation to a collective group identity, which is often socially constructed. This means that a generalised view of an individual’s identity, based on their perceived association with a group, may be formed and may lead to harmful stereotypes, disadvantages and discrimination.

Inclusion – the creation of a learning, working and social environment that is welcoming, which recognises and celebrates difference and is reflected in structures, practices and attitudes.

Inclusive language – refers to non-sexist language or language that “includes” all persons in its references. For example, the statement “a writer needs to proofread his work” excludes women due to the masculine reference of the pronoun. Likewise, “a nurse must disinfect her hands” excludes men and perpetuates the stereotype that all nurses are women. Therefore, unless a sentence refers to a specific person, it is better to use language that is inclusive of all. This is especially important in policies and procedures. Also see the ‘Gender neutral’ definition.

Intersectionality – the idea that an individual’s identity consists of various biological, social and cultural factors, including race, ethnicity, gender, religion and sexual orientation etc, and that each of these contributes to their overall identity and to who they are as an individual. The theory of intersectionality was originally coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw, an American civil rights activist, to describe the specific inequalities faced by African-American women. The term is now used more broadly, and a single person may experience multiple forms of discrimination and systematic social inequality as a result of belonging to more than one social category simultaneously. It may also mean that they experience privileges or disadvantages because of different aspects of their identity. They may experience barriers or even be excluded from one particular group as an indirect result of their identification with another. Also see the ‘Lived experience’ definition.